Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre

1986

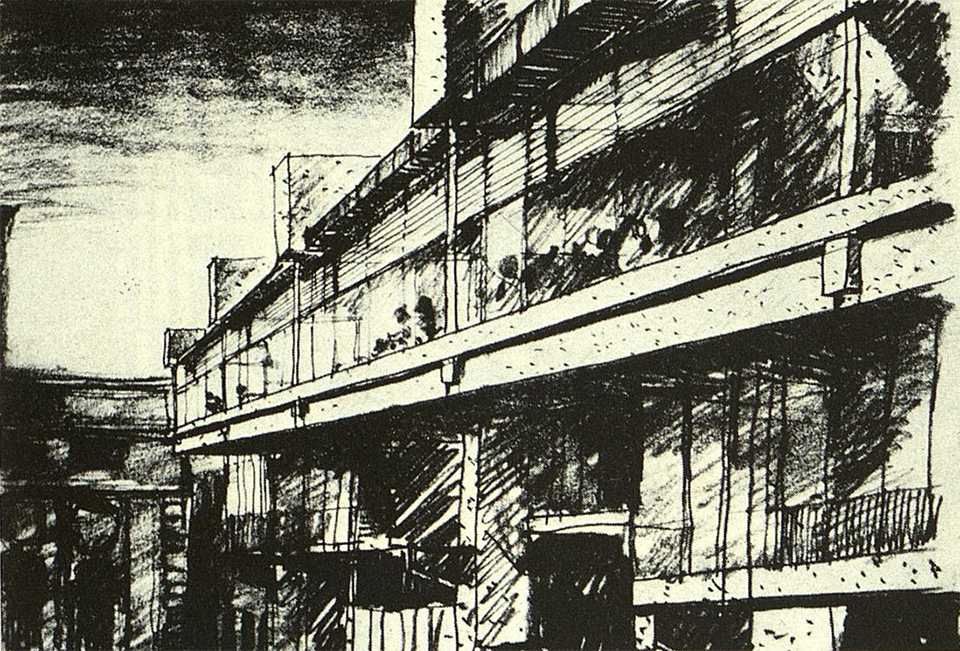

The Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre is surprisingly under the radar as far as aficionados and enthusiasts of British modern architecture are concerned. It was one of the most prominent government commissions in the latter half of the twentieth century. Completed in 1986, its starched civic modernism might be considered to suffer from stylistic time lag, although it perhaps owes a small debt to the hi-tech movement. Powell and Moya were briefed in 1975 though, before full blown Po-Mo had taken hold and there is something about building Westminster that demands a certain restraint and pseudo-Gothic inflection as evidenced by Hopkins’ Portcullis House (2000). John Winter, writing in the AR, was of the opinion that Powell and Moya’s work more generally had a ‘gentleness’ and ‘ an avoidance of the grand gesture that is, perhaps, rather English’ (he was referring to Pevsner’s interpretation). He concluded that, by building thoughtfully, one need not concern oneself with ‘petty fashions … propagated in the media’ [1]. Project architect James Hurford guided this complex job through its 12 years of design and construction, from 1974 to 1986. The building occupies a prominent corner, diagonally opposite Westminster Abbey and backing onto the Foreign Office, which makes its relative obscurity even more curious. William Whitfield won a competition to design a conference and office scheme on the site in 1961, but shortly afterwards Leslie Martin was commissioned for his bold plan to rework the entire district and recommended a building much larger than Whitfield’s winning design. Martin’s megastructure too remained unbuilt and thus the scheme was revisited. Nicholas Ray, writing for the AJ in 1986 referred to Hidalgo Mayo’s early sketch of the façade as ‘a confident exercise in tasteful modernity’ [2], which some may consider a back handed compliment. The sketch set the scene for the dominant third floor that housed the principal conferencing facilities. The floors above and below were set back, the lower three storeys a mix of lead clad loosely arranged bays of various protrusion, giving the building a pavilion like quality to its front whilst the flanking facades made an attempt to address their respective streetscapes. Perhaps the architecture was condemned to its background quality as it was never likely to compete with the ritual pomp and circumstance of its religious and state neighbours. Nor was a government conference centre likely to be a bold or brash as its commercial cousins. Nonetheless, this late flowering conservative modernism has aged with grace and is worthy of more than a second glance by those who appreciate these things.

[1] Architectural Review, June 1986

[2] Architects’ Journal, 15 October 1986