Czech and Slovak Embassies

1970

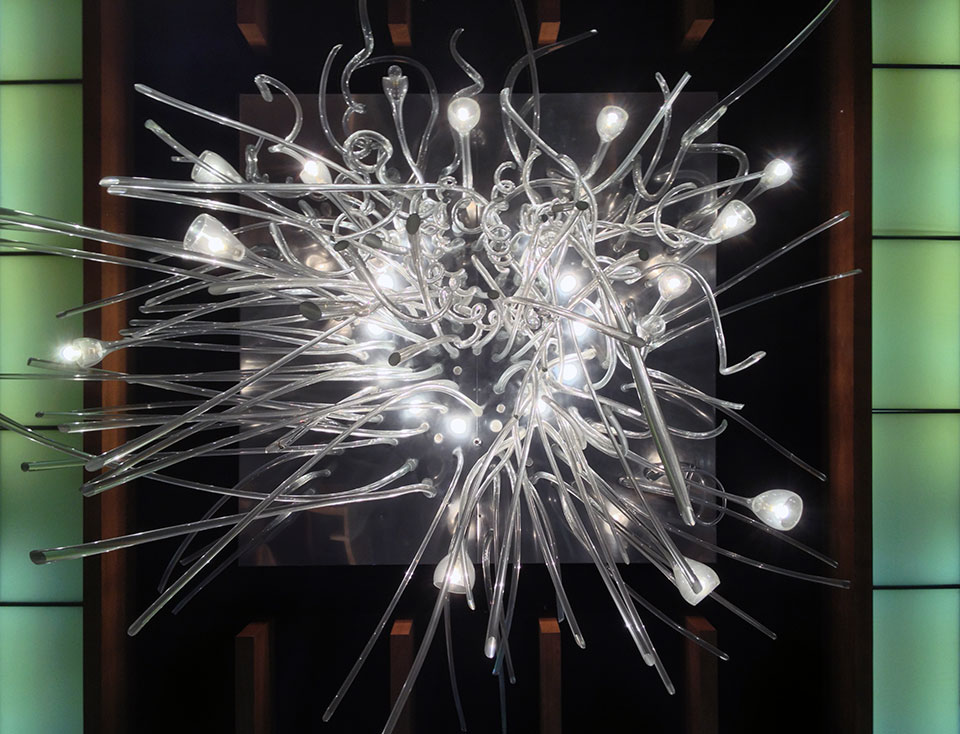

As observed by Concrete Quarterly, ‘Czechoslovakia has long had a reputation for good design’ [1]. Of course, in 1993, Czechoslovakia split into the two sovereign states of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Conveniently for the ambassadors of each, the original scheme was designed in two discrete blocks and was readily subdivided. In this sense one might suggest that the Slovak’s won out – they took the smaller of the two buildings that was originally the embassy itself. The other block, seven storeys facing onto Notting Hill Gate, was predominantly used for administrative and residential purposes. The now Slovak Embassy, facing Kensington Palace Gardens, housed a reception hall, private dining room, a basement cinema, lounge and conference room. As such, it was lavished with attention both in its architectural expression and in the commissioned artwork that adorned its interior. A sculpture by Eva Kmetová, light fittings by Professor René Roubiček and paintings by Adriena Simotova were all set against highly specified Iroko veneered beams, leather lined walls, ribbed and bush hammered concrete, paviors made in Czechoslovakia and dark blue engineering bricks – a robust opulence seems a fitting description. Attribution for the overall design is hard to pin down – the AJ records ‘Jan Sramek, Jan Bocan and Karl Stepanski, of Betta [elsewhere ‘Beta’] Atelier, Prague, working in conjunction with Sir Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners’, whilst Concrete Quarterly lists the same names but credits the Czech office as ‘Architects PVU Prague’. What is agreed upon is that Jan Bočan was the principle designer and that he spent six months in the office of RMJM working up the technical details. Originally intended as an entirely in-situ construction, a significant amount of precast eventually made its way into the scheme and was not without its detailing issues, particularly in the characterful composition of the smaller building. This was described as having ‘a middle European generosity and formalism which is attractive because of its strangeness, yet disturbing to British architects used to old fashioned functionalism’ [2]. The most strikingly designed element of the larger block, which has a much more rational expression of its structure, is a curved concrete wall facing Notting Hill Gate by sculptor Stanislav Kolibal that is similarly shaped in the interior but with a fine tooled finish. Bočan recalls that their aim was not to represent the contemporary Czech government administration, but to make a building that would outlast and supersede any association with a particular political system – it is safe to say that they succeeded. The building was the recipient of the RIBA award for the best building in the United Kingdom by foreign architects in 1971. To my mind this is one of the finest brutalist schemes in London and is a highlight of the annual Open City festival that should not be missed.

[1] Concrete Quarterly, No.83, October-Decmeber 1969

[2] Architects’ Journal, 9 July 1969