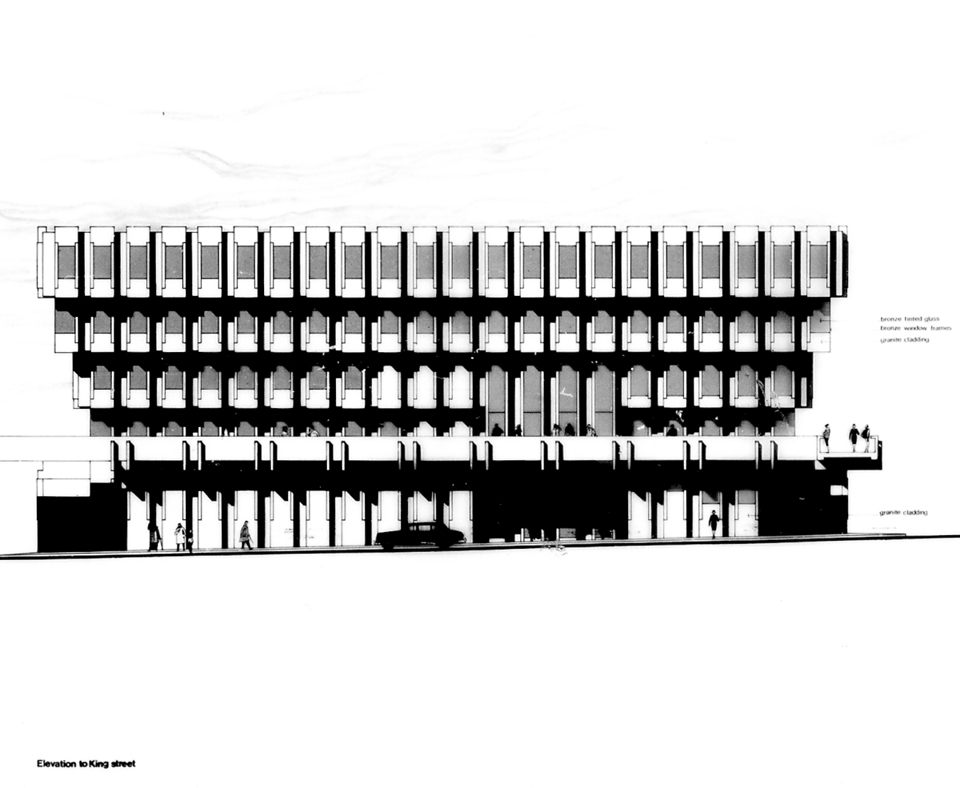

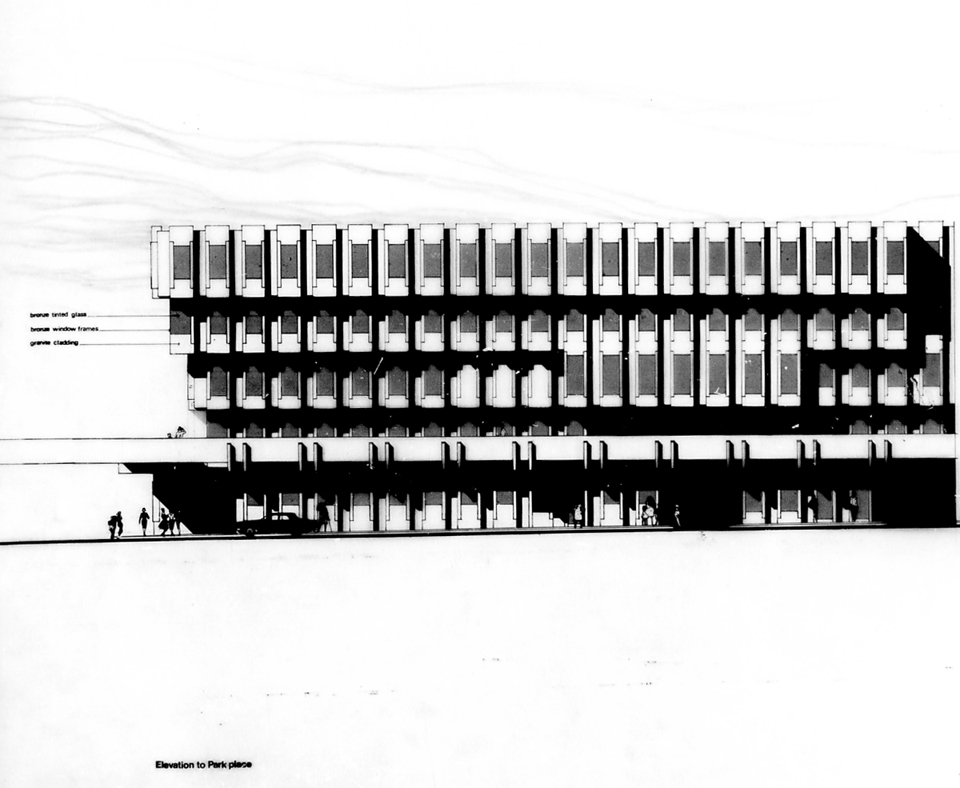

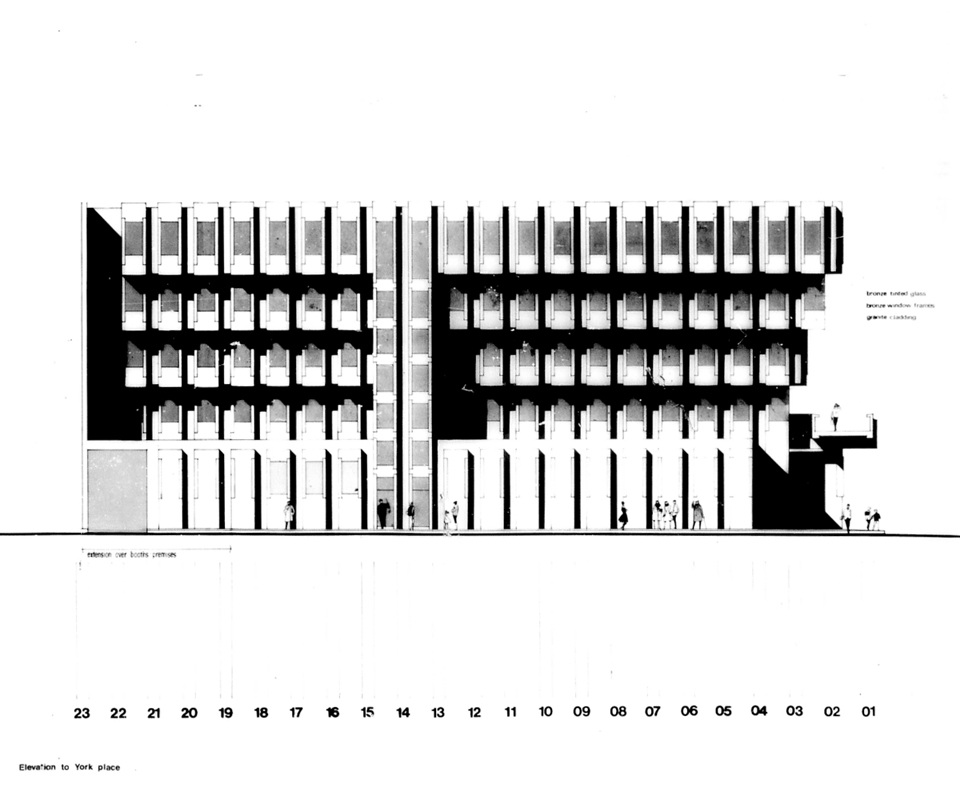

Bank of England

1971

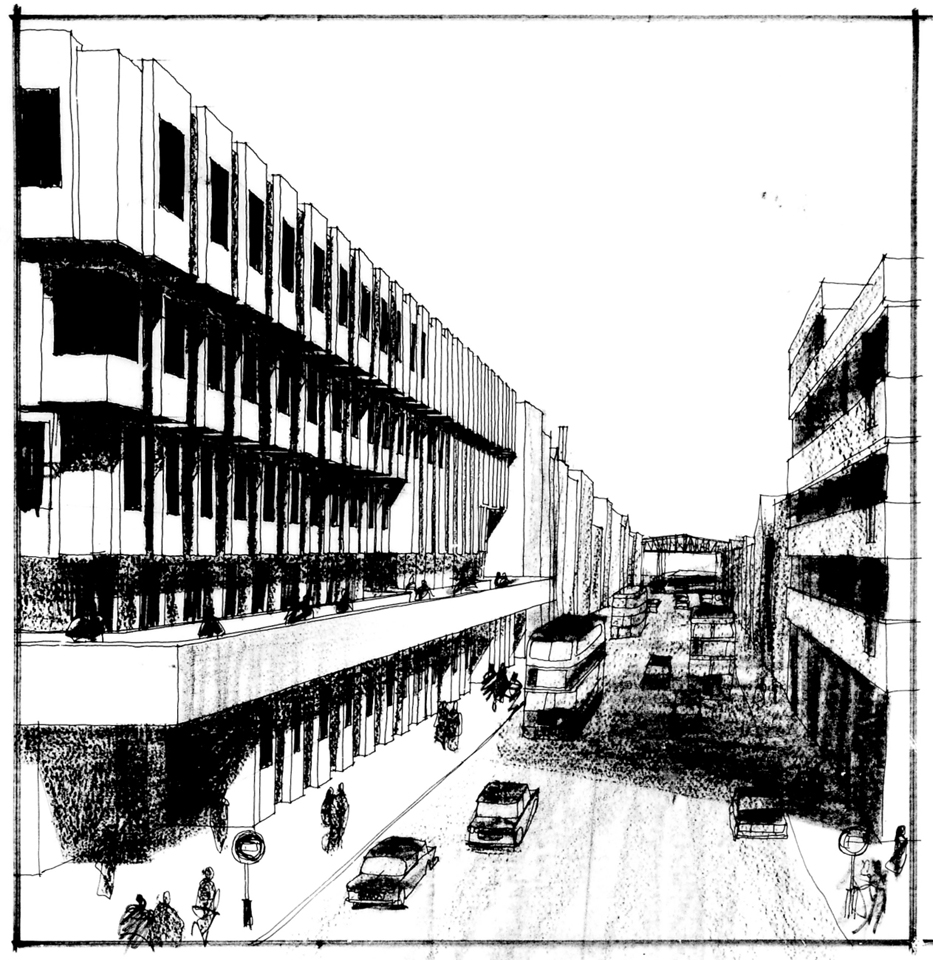

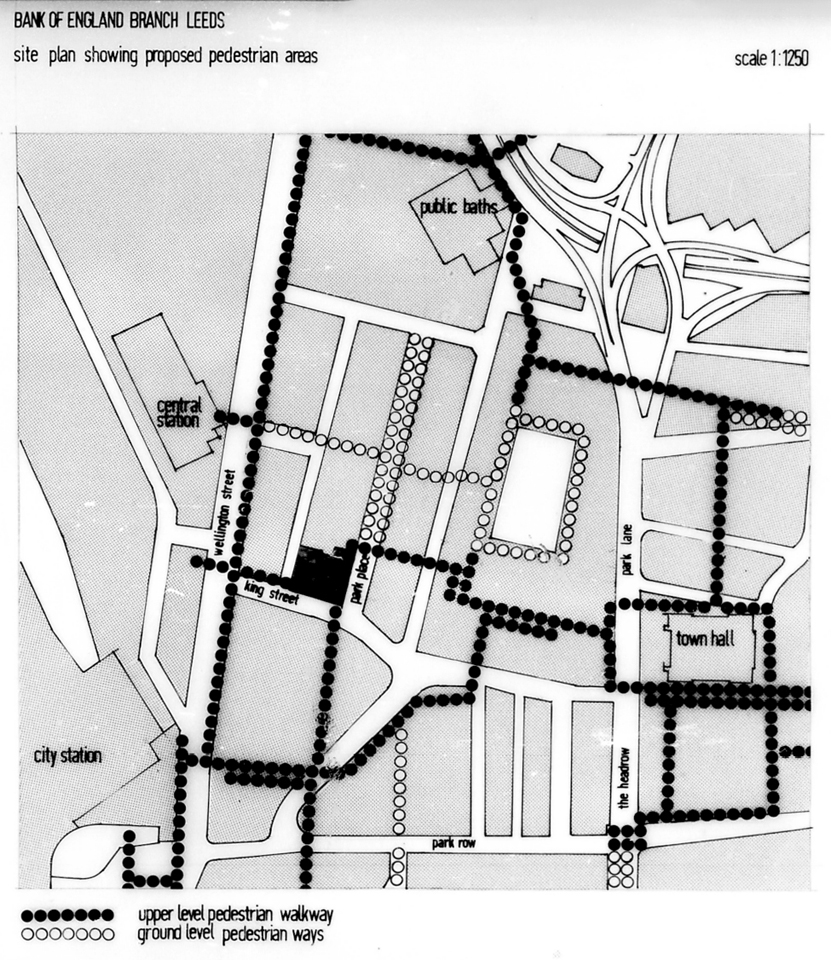

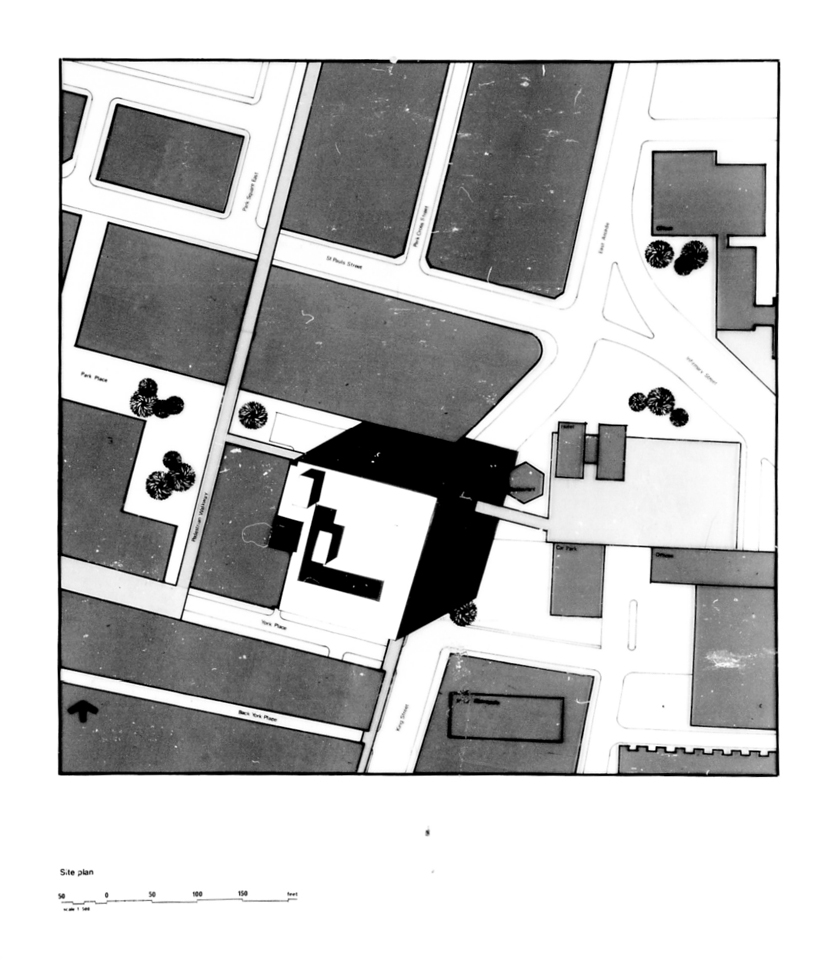

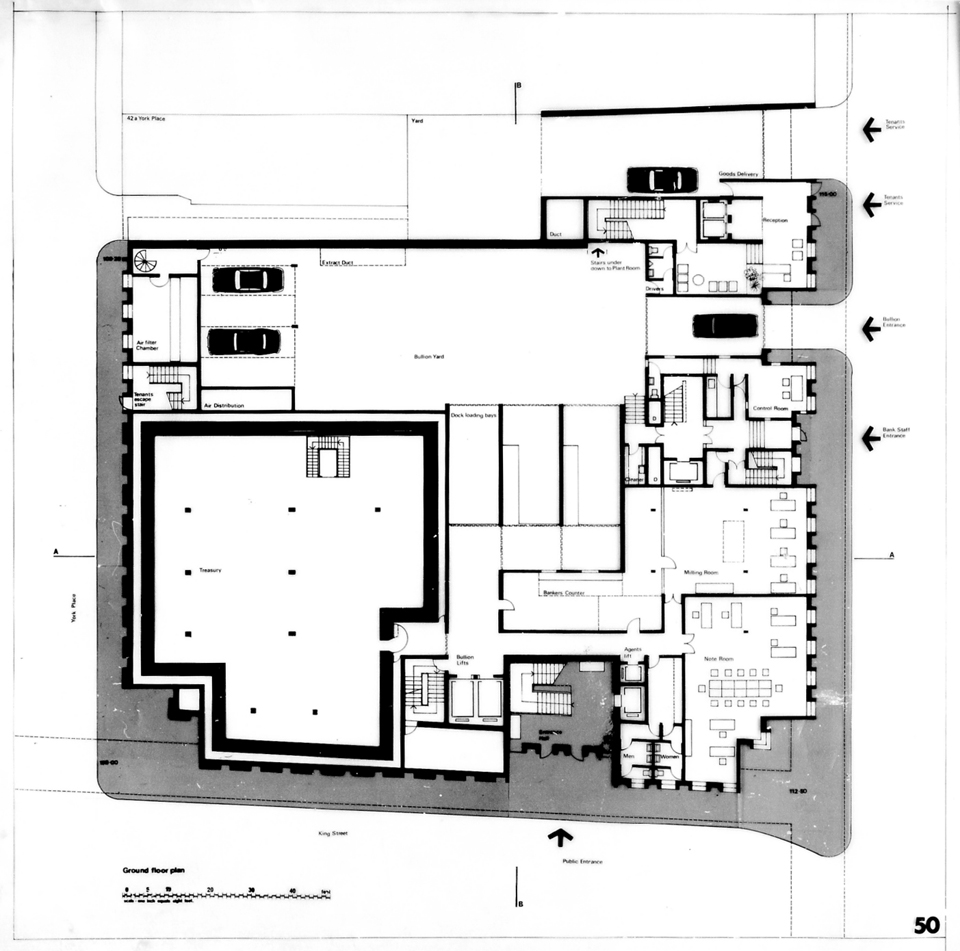

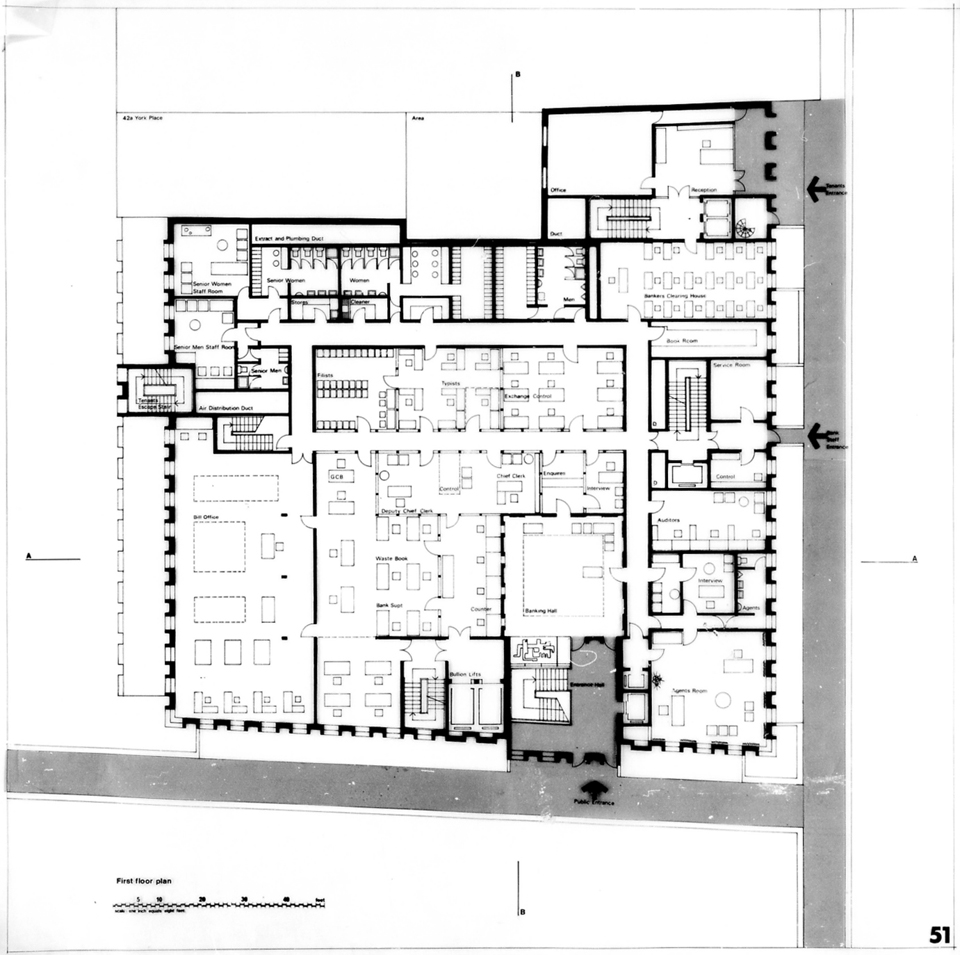

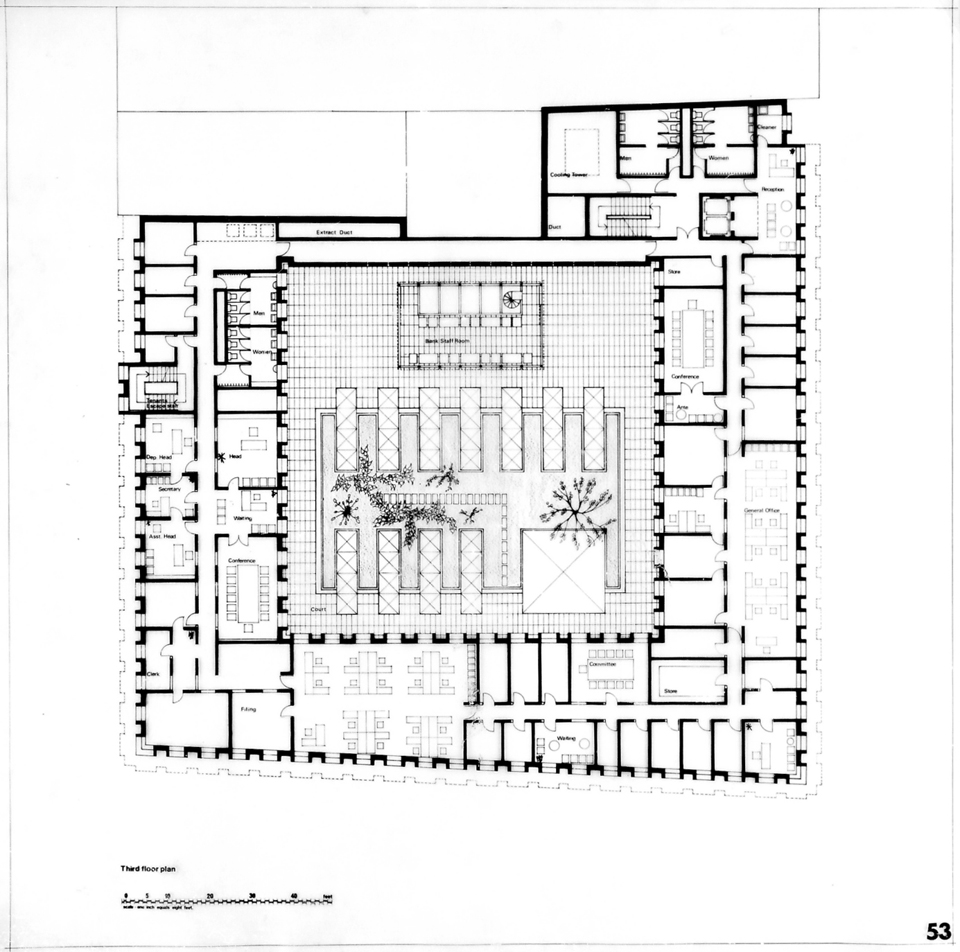

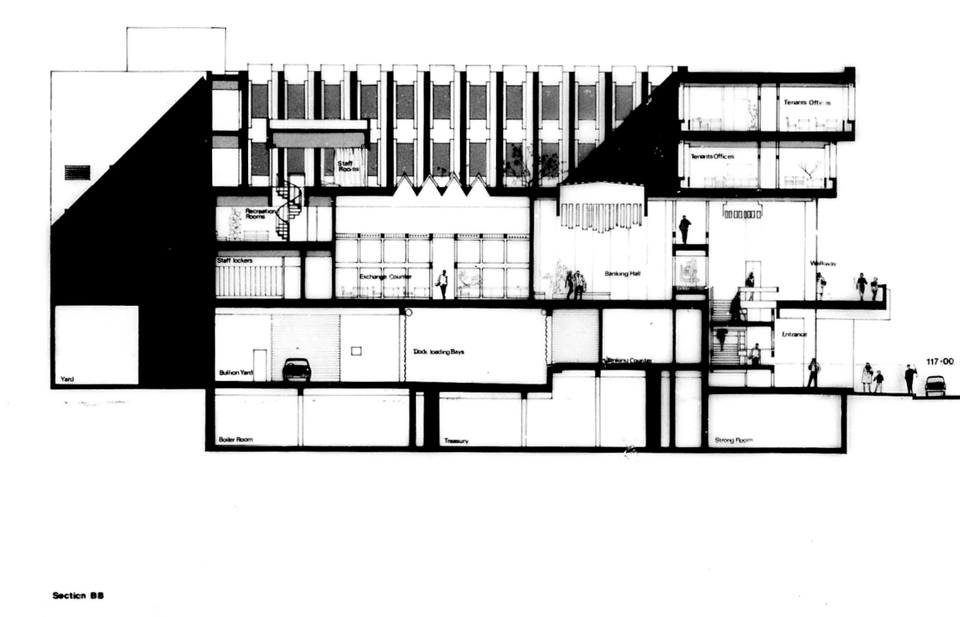

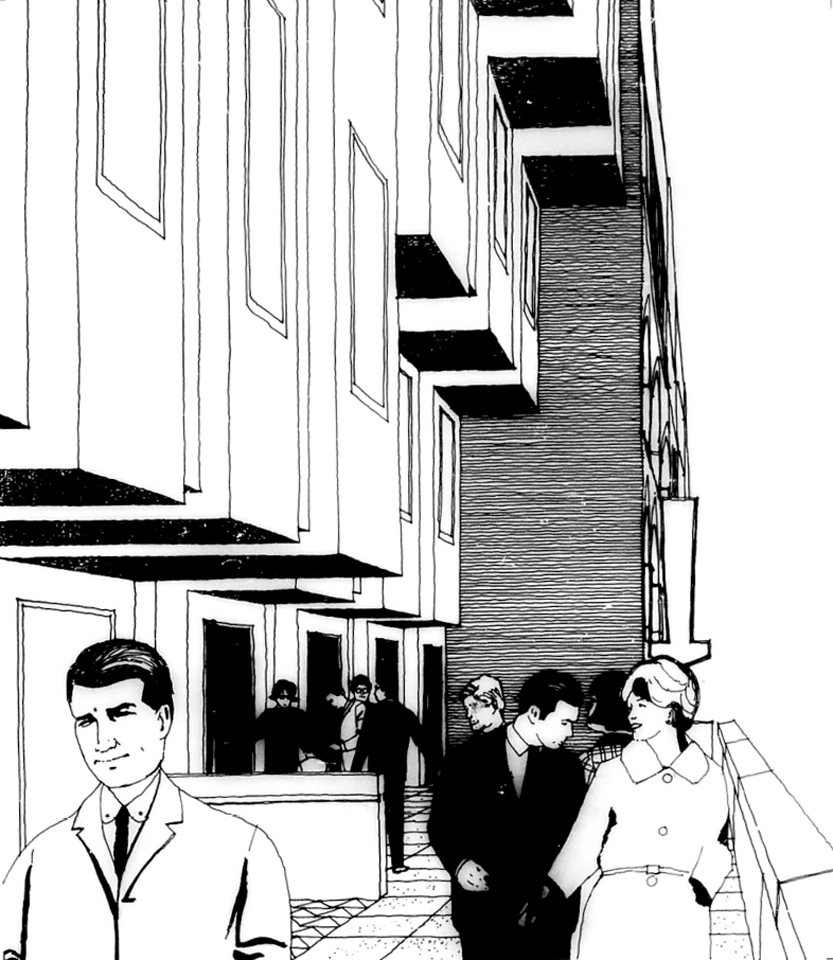

Despite its obvious quality, the Bank of England regional headquarters, like the others built at the time, did not feature in the architectural press. A search of the RIBA library reveals only one article, published in the regional journal Yorkshire Architect - these days a rare commodity. One may only assume that it was the security demands on the building type that led to some sort of embargo. In the latter half of the 1960s, and partly as a result of the 'Great Train Robbery' of 1963, British banks attempted to limit the movement of money around the country by establishing regional bullion centres with reinforced basement vaults. The Bank of England embarked upon a programme of rebuilding their key branches in Manchester, Birmingham, Newcastle, Bristol and Leeds. The Leeds branch was constructed in 1969-71 to the designs of Building Design Partnership (BDP) with Bill Pearson as partner in charge and Bob Greenslade as project architect; Greenslade was subsequently succeeded as project architect by Ken Appleby when he was promoted and went to run BDP's Belfast office. The design was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1968. The building was constructed on the site of a warehouse of 1862 designed by Cuthbert Brodrick, which was demolished in 1967. The scheme was, in effect, two buildings, the Bank of England’s functions were housed from the basement to the second floor and the upper two floors were to be commercially let. The site was part of the Comprehensive Development Area (CDA) at the corner of King Street and Park place and, as such, was required to integrate with the proposed Buchananist elevated pedestrian walkway that, inevitably, never actually came to be. However, the principal entrances were designed to be at the first floor level. The building line was set back considerably on this floor to accommodate said walkway and the floors above gradually stepped out again until the fourth floor aligned with the building line of the ground. The context also informed the scheme, limiting its massing to five storeys to respect the existing building heights in the area. The construction was predominately in-situ concrete, with precast concrete for the perimeter walls. Other than the walkway, which was also concrete, the external surfaces were all clad in a warm grey Cornish granite: ‘bronze, toned to the colour of an old penny’ that matched the period bronze tinted glass.