Mondial House

1978

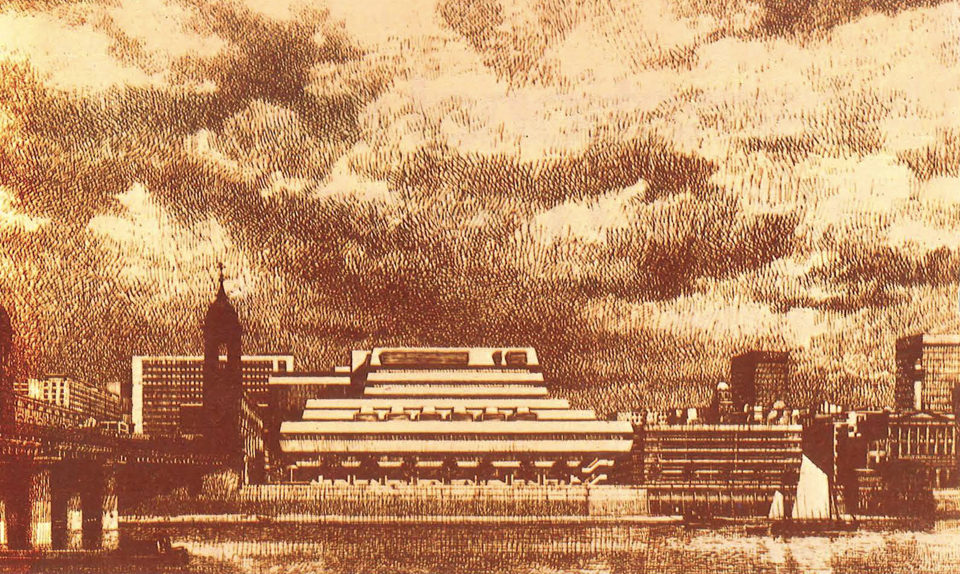

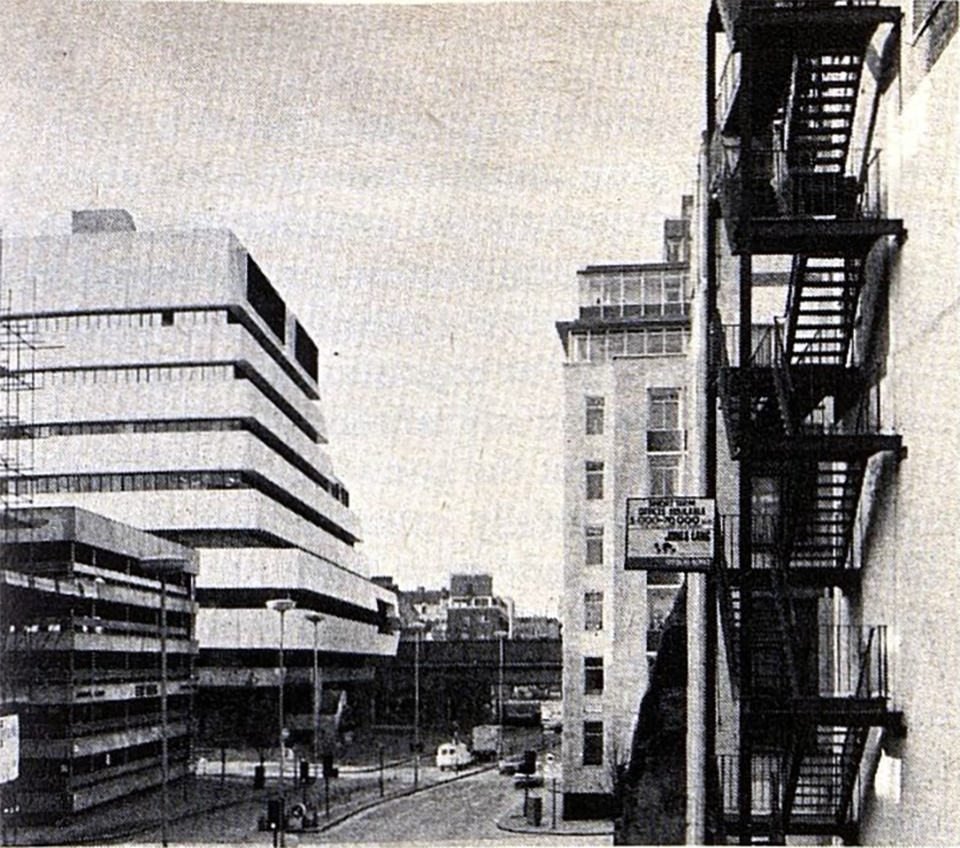

On completion, Mondial House was the largest exchange building in Europe. It was constructed in anticipation of a massive growth in international telephone traffic which, at the time, was doubling every four years. It was part of a £200m Post Office programme and one of three major exchange buildings completed in London at a similar time – the other two being Burne House in Marylebone and Keybridge House on South Lambeth Road. According to the architect, the building’s height was limited by planning restrictions designed to maintain unobstructed sight lines of St Paul’s Cathedral from London Bridge. Thus, the wide based, stepped profile was approved by the post office in 1969. An integrated fire station to serve the wider area was added to create something of a unique hybrid building type. Unsurprisingly, the building had a series of technical demands on its mechanical services provision and also had to consider the flood levels of the adjacent River Thames. The sheet piling used as a permanent formwork for the retaining walls of the basement eventually doubled up as a very efficient earth for the building’s complex electrical systems! Stylistically without precedent, Mondial House perhaps owes more to industrial design than it does to architecture. Adrian Gale, writing in the AJ compared it to a ‘multi-decked piece of audio visual equipment, control buttons arranged prominently along its projecting console and the combined speaker and microphone arrangement at its top’ [1]. From this historical distance and with more electronic kit with which to compare it, the white GRP cladding and curved geometries are more Commodore computer than Bang & Olufsen boombox. A sharp contrast between the walls and windows was enhanced by the solar reflecting film and blast proof plastic layers applied to the glazing, the whole skin somehow emphasising the functions within. The plinth level was resolutely concrete, but even this was stylised with curved profiles to hooded openings and a rather funky cast typeface pronounced the building’s name. Most of the building was demolished in 2006, but the fire station was retained and has become something of a legend amongst brutalism hunters.

[1] Architects’ Journal, 16 February 1977, pp.301-317.