Hilda Besse Building

1971

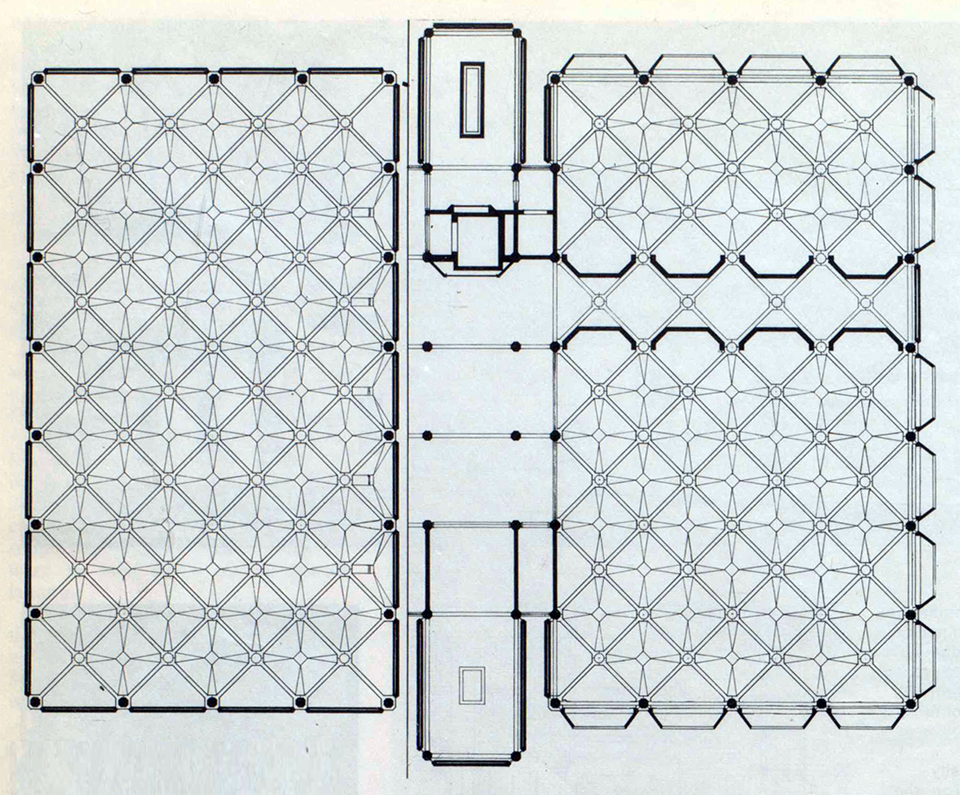

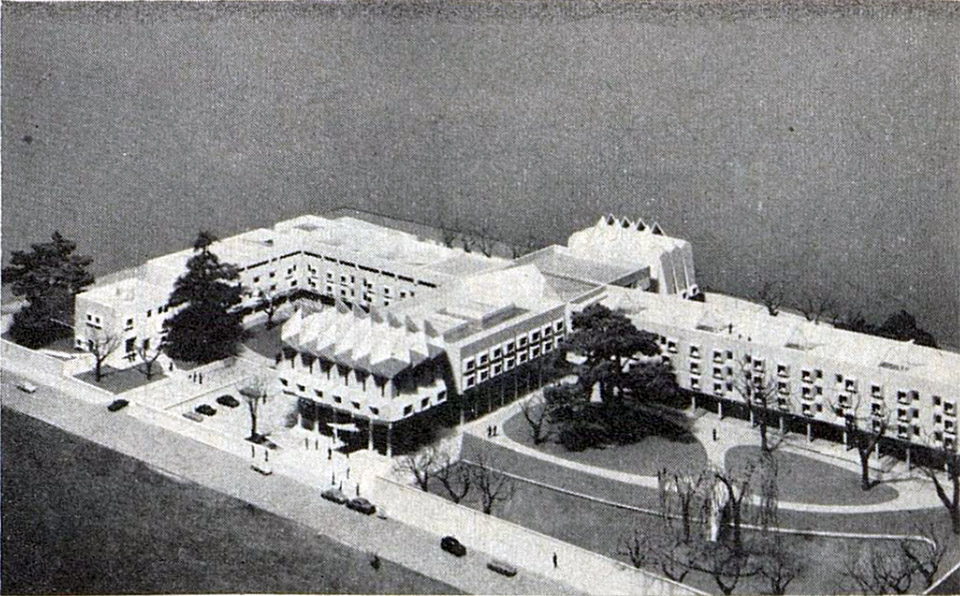

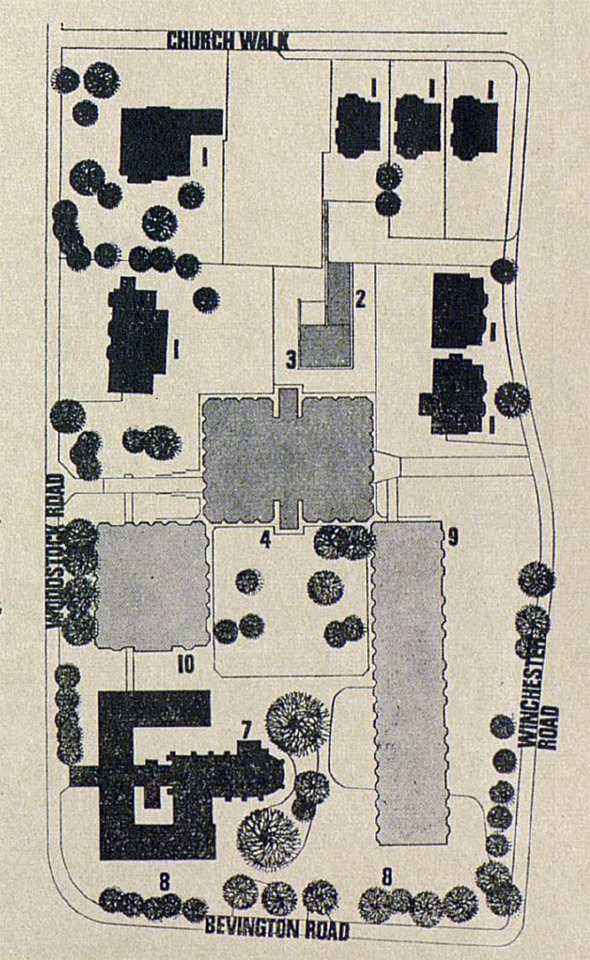

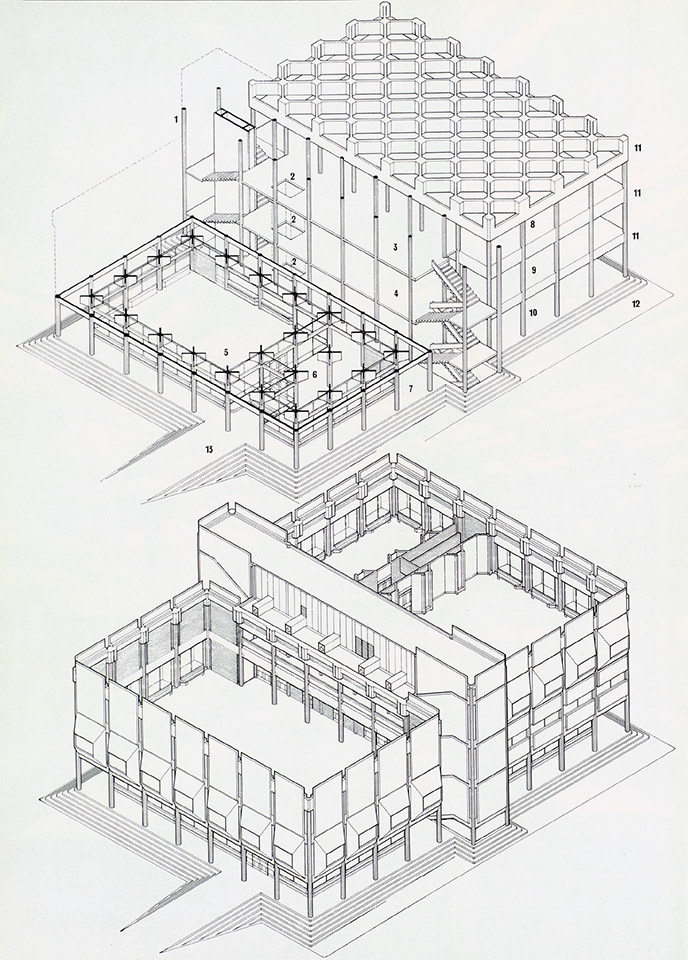

Headlined as ‘masculine; and ‘magnificent’, this robust exercise by HKPA was divisive at its opening [1]. St. Antony’s was a small college and this site, away from the city centre, was characterised by a series of unprepossessing Victorian buildings that once housed a convent. Unprepossessing was met with uncompromising in this standalone block that was supposed to be the first of a family of three new buildings in a masterplan drawn up in 1960 – the other two never came to be (see gallery for models and plans). Essentially the ‘hall’ for the college with a range of dining rooms and common rooms, its setting on a podium and its colonnade (a connection device for the anticipated additions) referenced tradition but its appearance blew convention apart. Now heralded by fans of brutalism, it is important to make the distinction between the heavy in-situ construction of its forebears and the finer realisation of this essay in precast concrete. Through the 1960s and 1970s, HKPA and others (notably Arup) developed a method of precast that had more in common with timber joinery than with poured mass. Every element in both the structure and envelope is precast and joints are articulated and interlocking. Moreover, the treatment of each element, in its mix and in its finishing was deliberate and considered. The internal columns in white concrete had mica added to the mix to make them glisten and they were polished to a near terrazzo finish. External panels used Cornish granite as an aggregate for a rougher appearance, piers were bush hammered and arches and pendentive units were needle gunned [2]. It is reasonable to compare St. Antony’s with their Wolfson and Rayne Buildings for St. Anne’s College, especially the ‘hooded’ windows, but this is an altogether more sophisticated composition. The impressive diagrid ceiling to the main dining hall invokes a vaulted tradition and achieves the scale and impact of those in the historic colleges. The fine treatment of the concrete was mirrored in the quality of the timber used sparingly on doors and floors. Externally, the distinction between structural members and cladding was expressed in thin glazed strips that separated the two. The partner in charge was John Partridge and the building was named Hilda Besse after the wife of the College’s major founding donor, Sir Antoine Besse. The recipient of RIBA and Concrete Society Awards at its completion, the building was Grade II listed in 2009 [3].

[1] Building Design, 9 October 1970, pp.10-11

[2] Architects’ Journal (Concrete Quarterly), 3 March 2005, pp.14-15

[3] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1393573?section=official-list-entry