Blackpool Police Station

1975

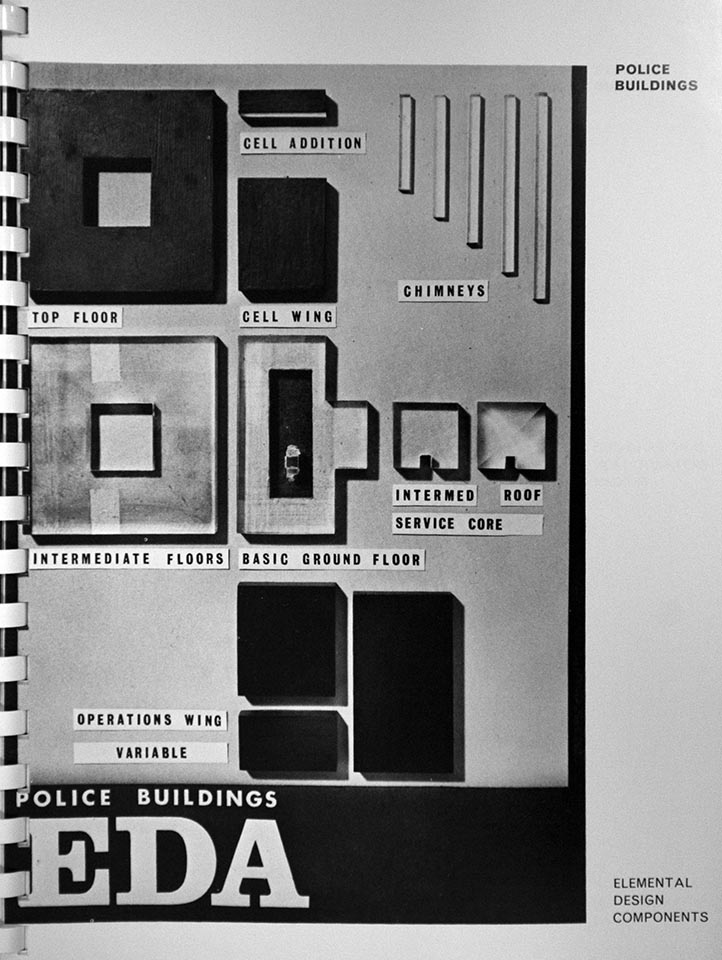

The design and construction of Lancashire’s police stations went through a thorough R&D exercise in the late 1960s and 1970s. The building type was explore using the ‘Elemental Design Approach’ (EDA) that had become a key part of the drive for efficiencies in the County Architect’s Department. The EDA was a method of simplifying brief requirements for particular building types and had evolved from early studies of homes for the elderly, using a rationalized traditional (RatTrad) construction system. Lancashire’s building system in concrete was known as GRID, developed in house and celebrated as the ‘first and only serious industrialised building system north of Nottingham’. In the initial stages of the EDA the police stations were conceived as a kit of parts, the assembly of which would be specific to the particular site or programme – a divisional HQ in a town centre would require elements not necessary for smaller sub-divisional stations. The ‘Elemental Design Components’ consisted of operations wing, cell wing, basic ground floor, upper floor plates, service cores and chimneys. In the 1966-67 County Architect’s Report, various configurations of these elements were presented as physical models to demonstrate the ability of the system to meet the various types of station requirements. As the EDA approach was married with the existing concrete construction system the complete standardisation from the first floor upward was proposed. It was considered that this would permit the ground floor to be designed as site and programme conditions dictated. Despite the apparent brutality of the forms, the qualities of civic design and public realm were strongly articulated in the descriptions of the schemes, the ‘solid character’ of the new police HQ in Wigan (1973) was said to act as part of the town’s urban grain and to ‘close the vista from Millgate’[1].

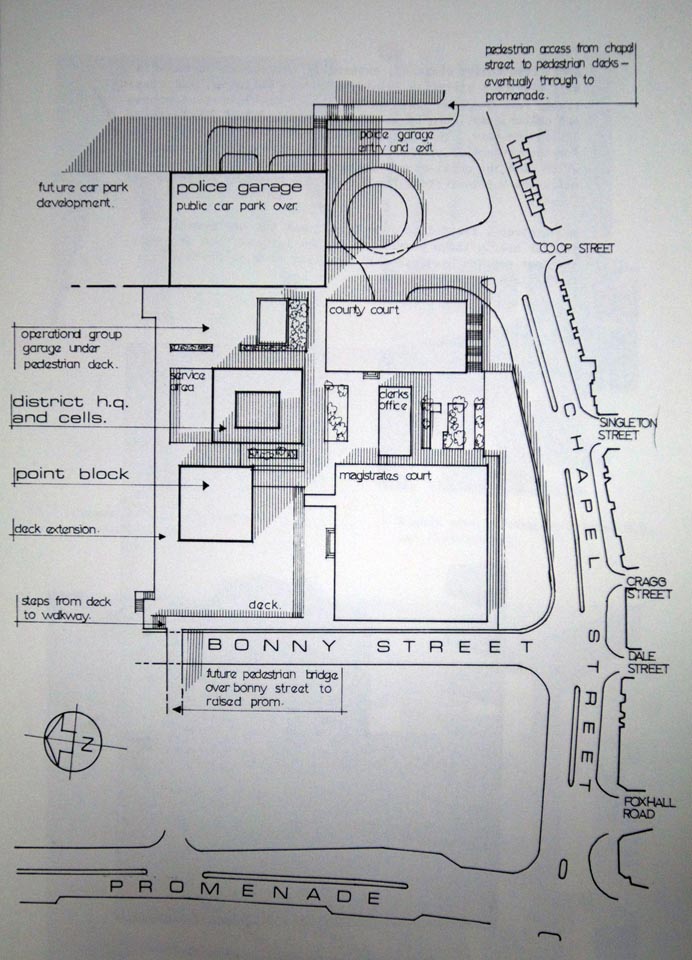

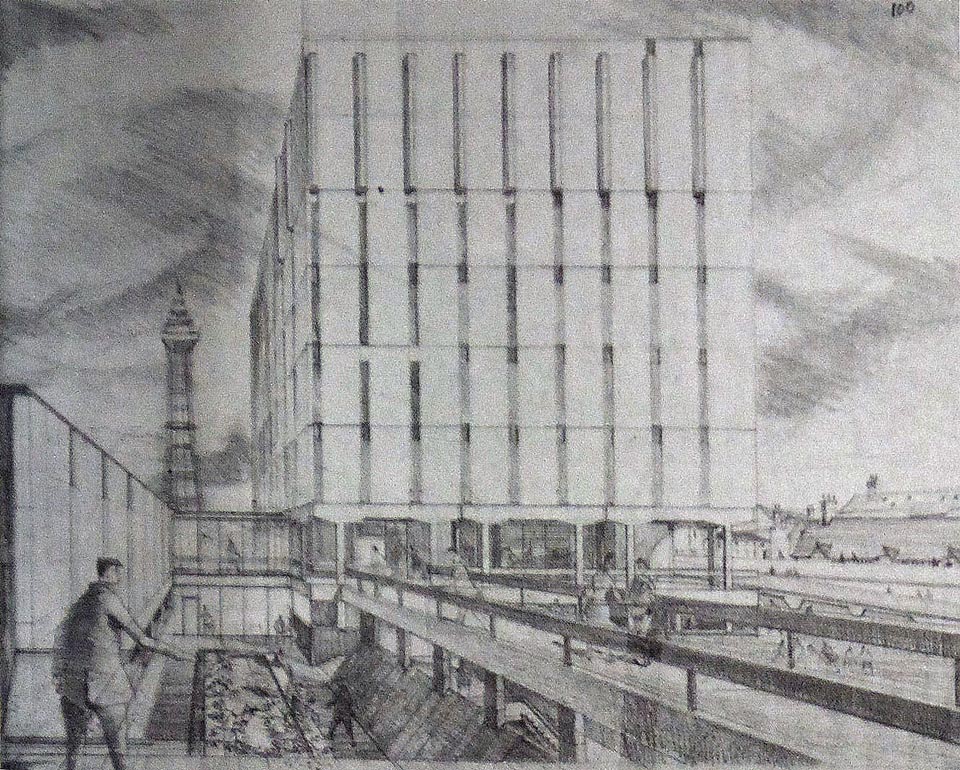

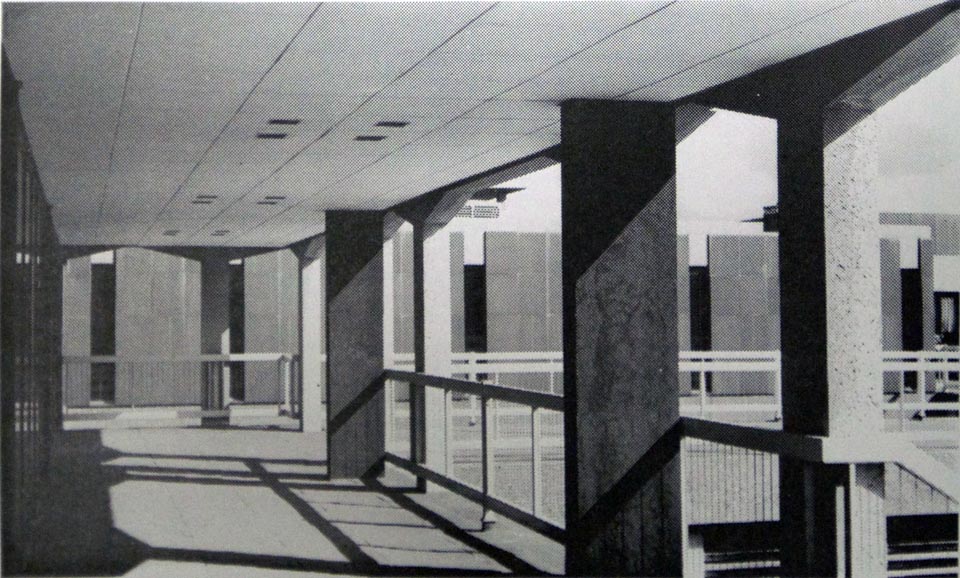

The most dramatic of the police stations to be constructed was the Divisional HQ at Blackpool (1975). The scheme was closely tied to other proposed developments in the town and was anticipated to form an integral part of the wider public realm. Adjacent to the police station were the earlier Crown and Magistrates’ Courts, designed by local practice Tom Mellor and partners, and a new multi-storey car park to serve the town centre [2]. The concrete panels of the station were made from specific sand and aggregates to try to match the colours of the Portland stone used to face the court buildings [3]. The primary access to the station was via a raised pedestrian deck, composed from a series of landscaped plazas between the formal elements. Sunken landscaped gardens were used to bring light into deeper areas of the plan on the ground floor. In collaboration with the local authority the entire scheme was intended to knit into the rest of the townscape by the provision of bridge links and further development to be procured by Blackpool Corporation. Some of this connective tissue was realised, but the piecemeal removal of various components mean that the high level plazas, now devoid of anything remotely green, have a dystopian atmosphere. In a Buchanan Report meets Logan’s Run landscape of chamfered and diagonal hard surfacing, the elevated squares now only link the low slung horizontality of the courts against the keep like monolith of the station office tower. The potential for the failure of the public realm was recognised by the architects who acknowledged that without the full delivery of the ‘planning concept’ by the Corporation, the buildings were ‘to some extent, isolated from the public and the Promenade’ [4]. The fortified appearance of the police stations did not escape the attention of the public either; apparently the question ‘are the police to be issued with bows and arrows?’ was not uncommon [5]. The secure sentinels were also built in Morecambe (1971), Preston (1972) and St. Helens (1973), bringing the total number of police stations built using the GRID system to six.

From today’s perspective it is easy to see how these structures were perceived as authoritarian. The intent of the architects was to allow the ground floor to seamlessly integrate with well-designed public space and for the solid upper elements to make positive contributions to the townscape within which they were set. In many respects these schemes would have sat comfortably in the minimal canon of the early 1990s and the term ‘monolithic architecture’ readily applied. Arguably before their time in aesthetic, yet not necessarily wholly original in their use of system building components, there is a clear sense that these schemes could not have existed outside of the very specific conditions in which they were formed. The post-war period and the national drive for renewal, Booth himself and his appreciation of architectural technology, the experimental and well-funded department and the structural associations between local government and the emergency services, all had their bearing on the aesthetic product.

[1] County Architect’s Report, April 1971 to March 1973, Lancashire County Council, p.119. Held at Lancashire County Record Office ref: CC/GR/22.

[2] Not every municipal building in Lancashire was designed by the County Architects’ Department. Tom Mellor and George Grenfell-Baines both received commissions from Simmons when he was County Architect, Booth continued this patronage. One such example is the library at Ormskirk. In conversation with Mrs. Dorothy Booth. Silverdale, Lancashire, 30 March 2015.

[3] County Architect’s Report, April 1975 to March 1977, Lancashire County Council, p.57. Held at Lancashire County Record Office ref: LCC/10/1/2.

[4] County Architect’s Report, April 1975 to March 1977, Lancashire County Council, p.55. Held at Lancashire County Record Office ref: LCC/10/1/2.

[5] County Architect’s Report, April 1971 to March 1973, Lancashire County Council, p.116. Held at Lancashire County Record Office ref: CC/GR/22.