Merseyway Shopping Precinct

1965

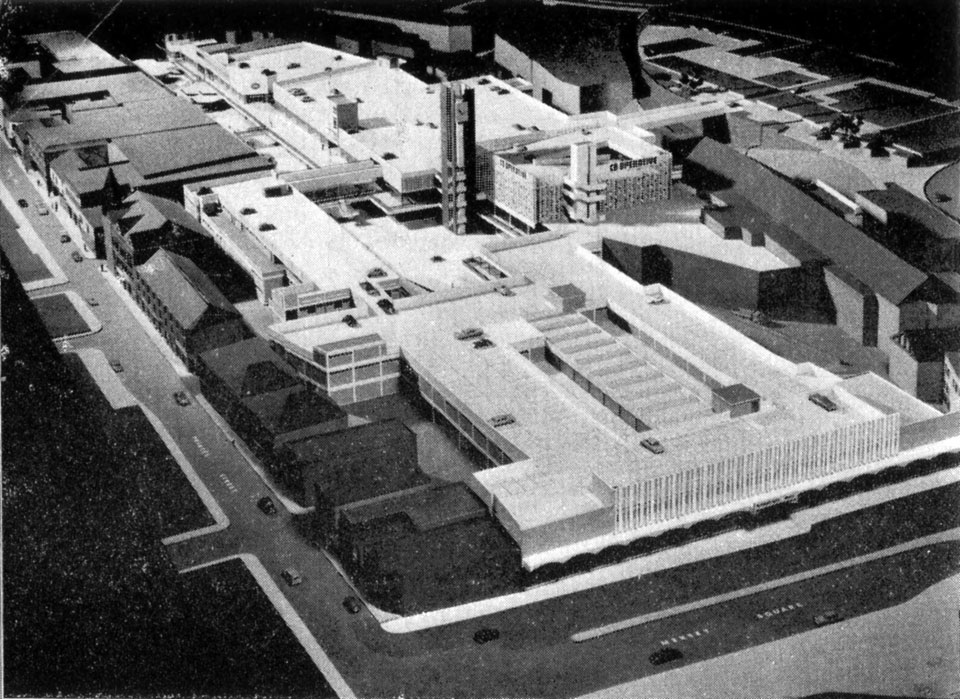

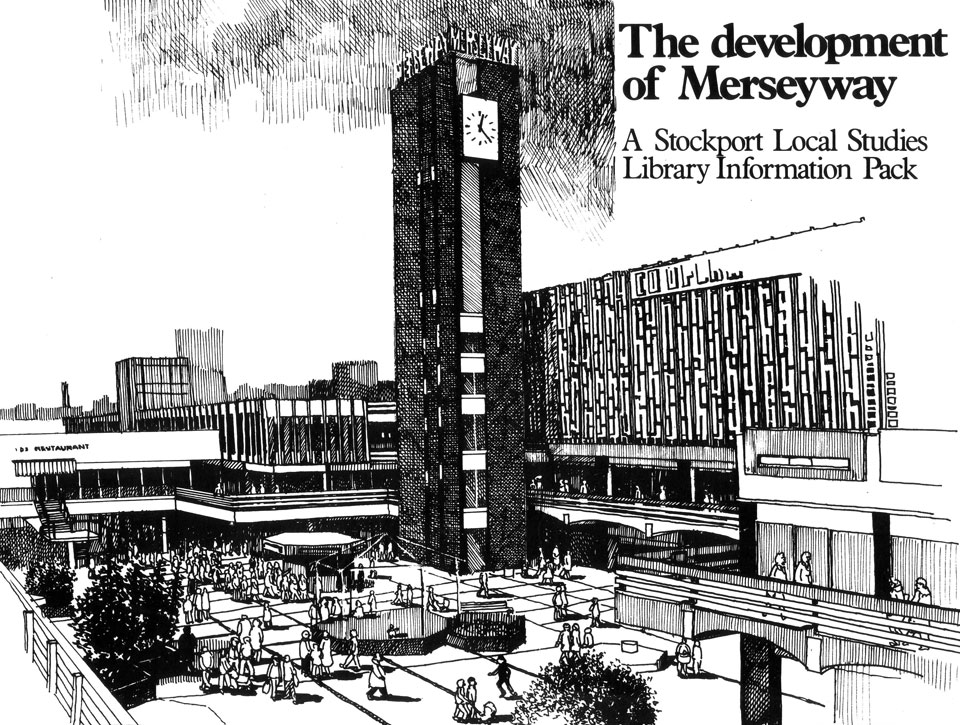

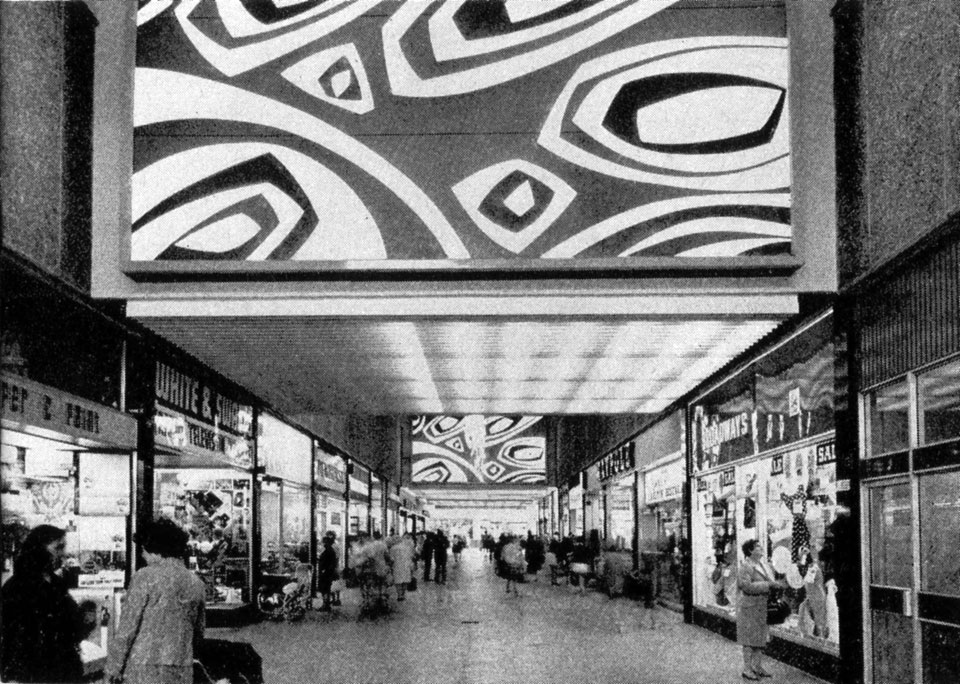

As with Manchester, Stockport had a post-war obligation to prepare a Development Plan. The preparation and subsequent ratification of the plan was typically a drawn out affair. The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act had made statute the preparation of such plans and in 1958, 11 years later the plan for Stockport was approved. Further amendments in 1966 and 1967 were incorporated into the 1969 Plan. Part of the plan included the ubiquitous by-pass, in this case the ‘A560 Urban Motorway’, later M63, later M60. This was designed to remove ‘noise and fumes’ from Merseyway and in the spirit of urban renewal provide a pedestrian precinct ‘where people can walk freely and safely without fear of being run down by intruding traffic’. The road which was effecticely a 1/4 mile long bridge forming a culvert beneath had only been completed in 1940 to ease congestion elsewhere. The scheme was developed by a consortium of interested parties who formed as Stockport Improvements Limited. In partnership with the Stockport Co-operative Society they agreed to coordinate new development so that they ‘would marry into a united scheme’. The architects were Bernard Engle and Partners in conjunction with officers of Stockport Corporation and the centre opened in 1965. The separation of pedestrians and cars, the service areas, the multi level street, the city block that negotiates difficult topography to its advantage, are all planning moves that are of the new, ordered and systemised, second wave modernism in the UK. The aggregate of the highways engineering, the urban planning and the shifting demands of retailers frequently arrived at a form and order such as this. In this way Merseyway is unremarkable, it’s like many other centres in many other towns – consider the rooftop landscape of Blackburn. It is, however, typical and has been typically added to and adjusted during its life and presents perhaps the face of the last retail metamorphosis before the out-of-town really made the grade. The death of the mall and the typological morphology of the high street is very much a contemporary issue and seemingly headed toward a charity shop/coffee shop/outlet montage which is currently perceived as quite a negative composition, but probably has its own merits and possibilities in terms of the life of the street and community cohesion, if addressed positively and with the correct enquiry. Merseyway as built was actually quite modest in scale when compared to Sam Chipperfield's rampant Arndale Centres that swallowed whole towns throughout the 1970s. Nor is it necessarily of any great architectural merit, save that of its embedded art works. The only really flashy bit of urban theatre were the external travelators; just a glimpse of the future! They descended to the main square, which was conventionally flanked by a clock tower, but not that of a civic building, it belonged to the Co-op. The new premises of the Co-operative Society were designed by their prolific Manchester based architectural department and the car park was optimistically designed to receive a further floor of parking should demand necessitate. The new building was attached to their original shop and doubled the floorspace, making them the biggest single operator in the centre. The names of the other tenants in the 1970s is quite a nostalgic roll call; Woolworths, British Home Stores, C&A, Rumbelows all had their presence alongside survivors like Tesco and M&S.