Plastic Classroom

1974

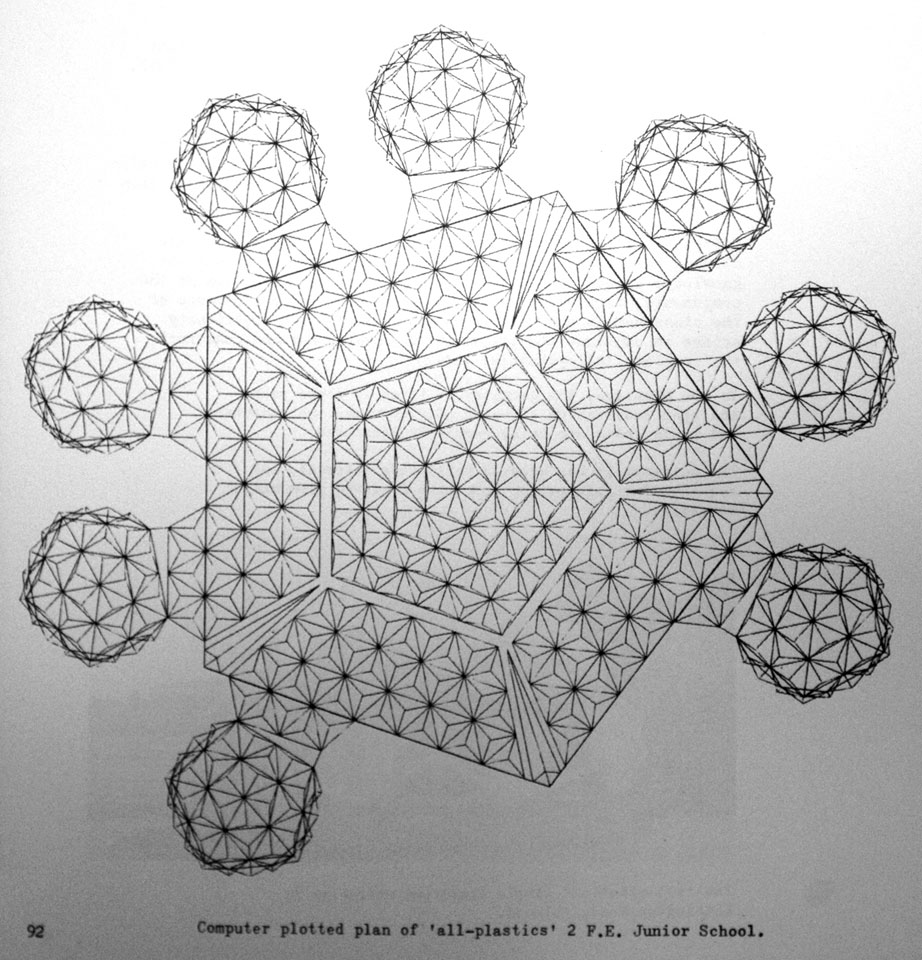

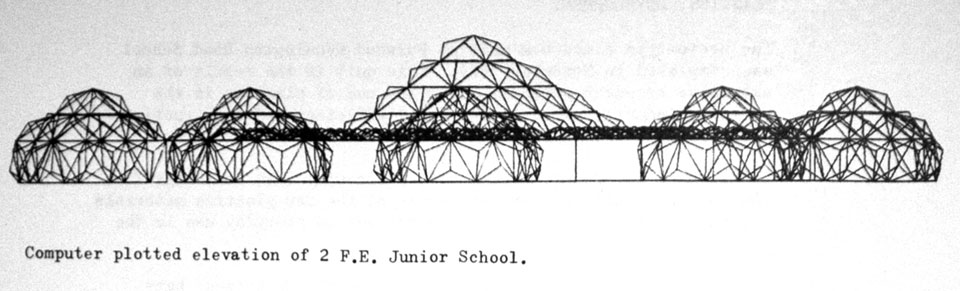

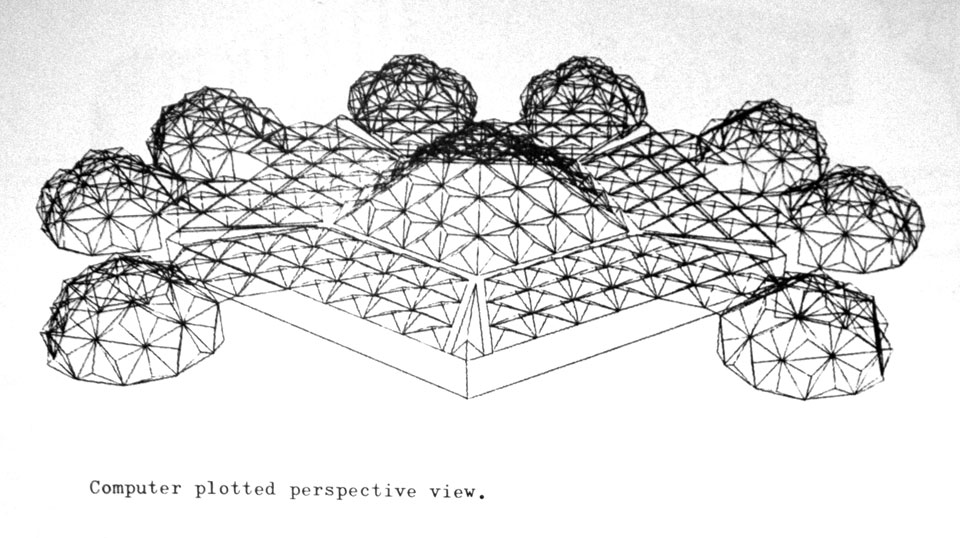

The principle of industrialised building for schools had almost become a doctrine under the direction of Stirrat Johnson-Marshall as Chief Architect for the Ministry of Education; its logic was reinforced by successive Building Bulletins and design guidance. The consortia ‘were intended to save time and money’ and ‘to give local authority architects everywhere the chance of building more and better schools’.[1] Lancashire had evolved new timber and concrete building methods for schools, so it is no surprise that a school should be the testing ground for a new plastic construction system. The aim of the department was to build an entire school from the plastic system at a site in Thornton-Cleveleys, but, before they did, a prototype single classroom was constructed as an addition to a Victorian primary school building on Kennington Road in Fulwood, north of Preston

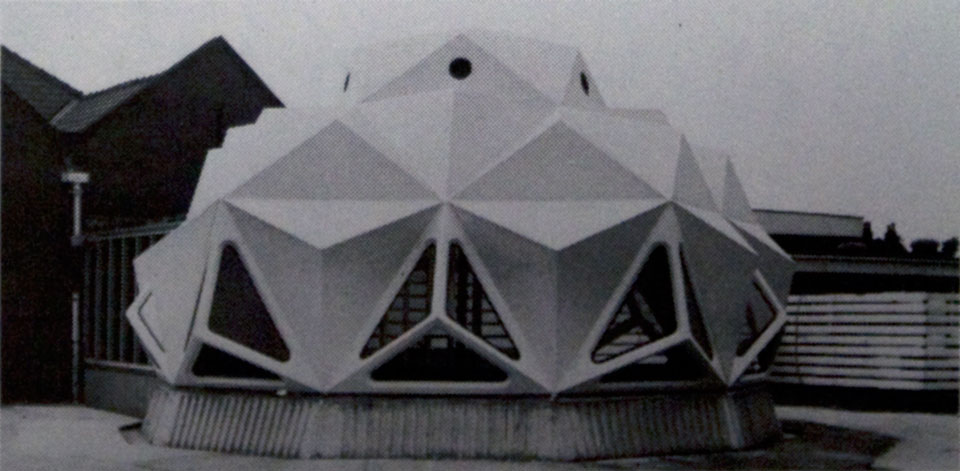

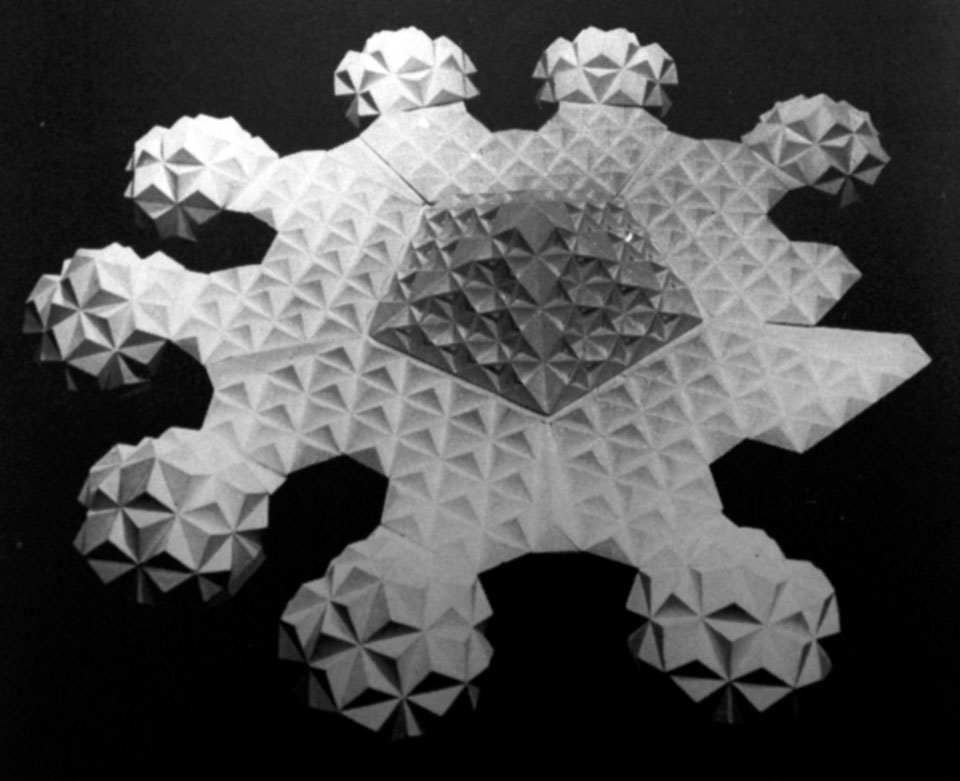

The 16ft (4.8m) tall structure was based on a modified icosahedron. A total of thirty-five glass reinforced polyester moulded panels came together to create the whole, which was bolted to a concrete pad foundation. The interior was lined with phenolic foam to provide insulation and achieve the requisite acoustic properties for teaching. The idea for the experimental building was credited to Roger Booth, but it was architects Ben Stephenson and Mike Bracewell who developed the material technology. Using a new phenolic foam system developed by Synthetic Resins Ltd. of Liverpool as a base and a GRP laminate face.[2] The system was tested to destruction by SRL in their laboratories and by the Warrington Research Centre and was demonstrated to ‘more than meet the requirements of the Fire Regulations’ and, in doing so, became the first all plastic building in the country to perform thus.[3] According to reports the children and staff were ‘very pleased with it’ as it allowed freedom of movement, was warm and had good acoustics.[4]

The experimentation also extended to the furniture as the new form of classroom, without walls or corners, demanded new ways of working and sub-dividing the space. In April 1973 furniture design consultants Macpherson and Kernaghan were appointed to liaise with the County Architect on the development of a new range of plastic furniture that was complementary to the construction system but that could also be rolled out across the county.[5] The most radical item in the range was a type of classroom ‘dresser’ known as the ‘main frame’. It was at once a room divider and storage device to which mirrors, pin boards and various storage units could be attached and it compensated for the lack of vertical display surfaces in the proposed structure. The first prototypes for the furniture were installed in the school in October 1973 and the 23 pupils and their teacher were able to partition the space as they wished.

The classroom was a rather strange juxtaposition against the Victorian primary school to which it was appended; it can only have been that the school needed space and the department needed to test the system that saw this awkward collision. The advanced nature of the system was mirrored in the way in which it was being developed, using three-dimensional computer aided design software. The classroom was completed in November 1974, unfortunately the oil crisis of the same year put pay to any further development or realisation of an entirely plastic school.[6]

[1] Saint, A (1987) p.191.

[2] ‘In the round’, The Guardian, 26 November 1974, p.21; ‘School is first to use new grp system’, Environment (North West), October 1975, p.4. (Copies held at LSE Library).

[3] County Architect’s Report, April 1974 to March 1975, Lancashire County Council, p.91, LCC/10/1/1, Lancashire County Record Office.

[4] ‘In the round’, The Guardian, 26 November 1974, p.21.

[5] County Architect’s Report, April 1974 to March 1975, Lancashire County Council, p.116, LCC/10/1/1, Lancashire County Record Office.

[6] County Architect’s Report, April 1974 to March 1975, Lancashire County Council, p.91, LCC/10/1/1, Lancashire County Record Office.