Preston Bus Station

1969

Preston Corporation commissioned the new bus station in the early 1960s. The first schemes for the site were relatively modest and typical of other similar buildings of the period – single storey, extended canopies for shelter and an apron for vehicular circulation. By 1965 things had changed, the Leyland-Chorley area was disclosed in Parliament as one of the preferred sites for a third-generation new town to aid the sustained growth of the Manchester conurbation by providing new homes with good transport links to the regional centre. As such, a series of urban projects were announced and upscaled in anticipation of the linear polycentric ‘supercity’ of 500,000 inhabitants.

The site for the bus station was bombed in the war and proposals for its renewal were prepared by George Grenfell Baines (founding partner of BDP) as early as 1946 and exhibited in Preston’s Harris Art Gallery and Museum. Ultimately, Building Design Partnership were appointed as architects for the scheme that would be the transportation hub of the new city. Of course, this was the era of motor borne transport, Dr Beeching was culling the railways, oil was cheap and abundant and Britain’s first motorway, the M6, opened in 1958 and by 1965 ran for 111 miles connecting north Lancashire with south Staffordshire. Trans-European services ran from one end of the bus station and its internal character was partially akin to an airport departure lounge, albeit a little more draughty!

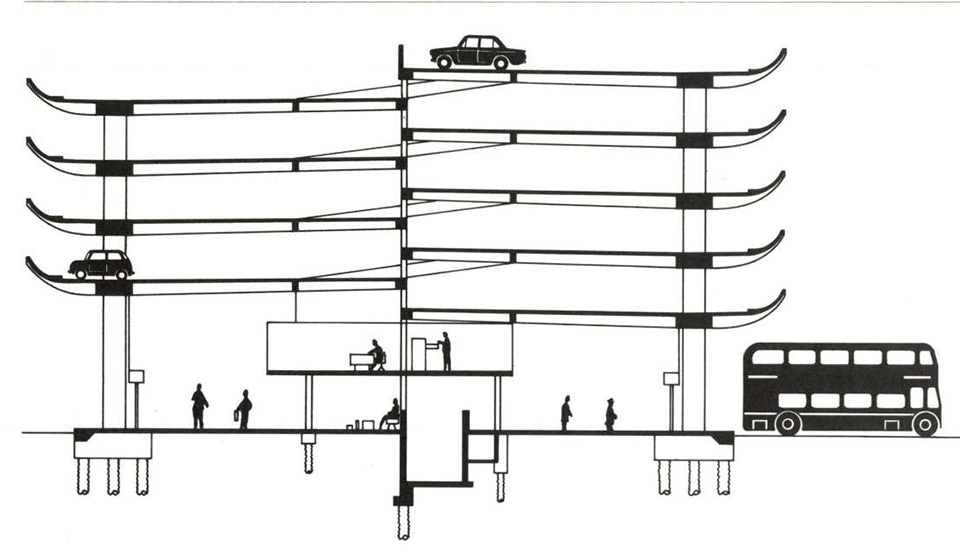

This new scale of operation and expected growth of population created the need for parking and interconnectivity. The multi-storey parking atop the double height bus station concourse was designed for 1100 cars and intended as part of a network of car parks around the town centre ring road. Buses and passengers were completely segregated. this was achieved by the use of subways and bridges that connected the bus station to the rest of the town, including the adjacent Guild Hall (RMJM, 1973), which was also pre-emptive of the expanded city. Departure and arrival gates for 80 buses were provided and marked by prominent backlit acrylic signs with orange numbers using the British Rail typeface, Rail Alphabet, designed by Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert - the same font was used throughout the rest of the scheme.

Despite its now iconic status as a standard bearer for British Brutalism, the form and mass of the bus station was primarily driven by economic efficiency, informed by the innovative architectural thinking of lead architect Keith Ingham. Its structural organisation was used a grid based on car parking standards. The 12.2 metre grid chosen accommodated 5 car parking spaces or three bus stands and was extruded along the length of the available site with vehicular access ramps at each end. The car park was organised on split levels, being the most economic, as the ramps become an integrated part of the circulation space of each level. This arrangement in turn governed the form of the area left for the passenger concourse at ground level. The curved form of the car park floor edges evolved after acceptable finishes to a vertical wall proved too expensive the curve was seen as a natural evolution of the T beam structure effectively just bent up to give the necessary protection to cars and pedestrians, removing the need for an additional canopy. The headroom beneath the cantilevers, of approximately 5.2 metres to allow the buses to park, enabled the creation of a central mezzanine level within the concourse where the offices of the various bus companies were housed. Beneath these were waiting rooms, shops, toilets and a café.

The construction is generally of reinforced concrete. Columns were cast in situ on pile foundations with beam edge units precast in glass reinforced plastic (GRP) moulds in an onsite factory. The decision whether to manufacture on site or off site was left to the contractor but, due to the scale of the available area, onsite proved very effective. The vertical circulation towers were faced with white tiles as were most of the common areas and the subways. The other finishes on the concourse were extremely durable, the floors were finished in black ribbed rubber tiles, the doors barrier rails and seats were all made from iroko, an imported hardwood. The perimeter of the concourse was enclosed almost exclusively by sliding door system two doors to each bus bay. Accessories like litterbins sign and poster boards were made out of GRP to bespoke designs. Keith Ingham went on to form a company called Glasdon That specialised in GRP street furniture, especially well known for their kiosk.

At the south end of the site a separate structure for taxis and private cars pick up and set down was designed. The hard landscape was predominantly granite setts, many of which survive today. The bus station was never really used to full capacity, but its high-quality finishes made for a minimal need for maintenance. Combined with cash strapped local authorities after the 1970s economic downturn, this led to much of the original building and its interiors surviving intact into the early twenty-first century. Of course, brutalism and concrete became shorthand for ugly in the popular imagination and the bus station was perceived as a financial albatross around the neck of the council who commissioned a regeneration plan that proposed its demolition – perversely BDP were at one point the contracted architects and may have been implicated in destroying one of their own best works! The building was twice refused listing before some dogged research by the C20 Society’s Christina Malathouni uncovered just how innovative the use of GRP moulding was and this met with a shift in attitudes concomitant with the rising popularity of post war architecture and the building was awarded Grade II listed status in 2013. Subsequently, following a competition, half of the bus station was closed, leaving forty bus gates on the east side active and the western apron was pedestrianised to allow surface level pedestrian connectivity to the city centre commercial areas. In so doing the pedestrian subways were filled in and closed, but the overall sensitive restoration of the building by John Puttick Associates won plaudits from peers and the public alike.