Central Library

1978

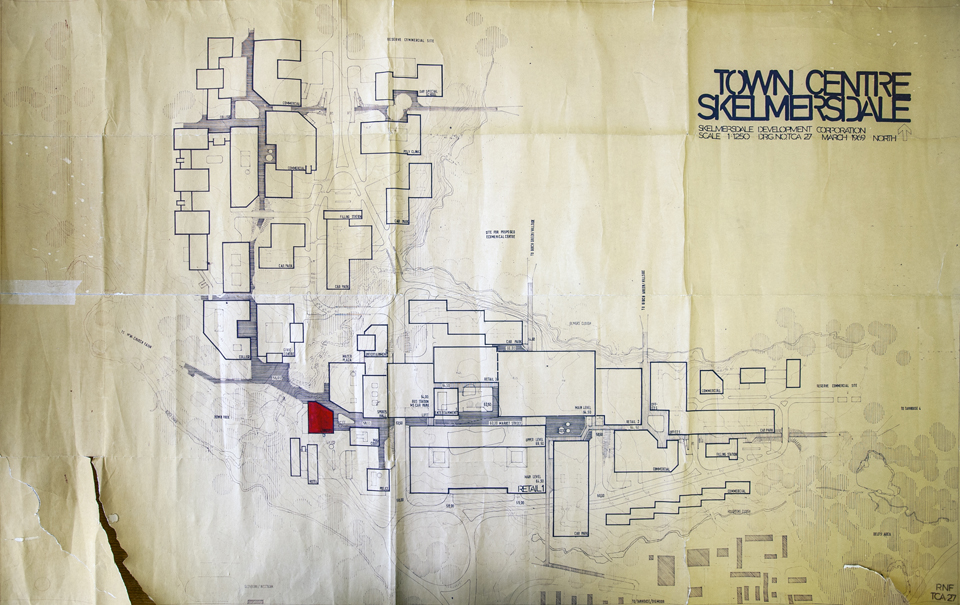

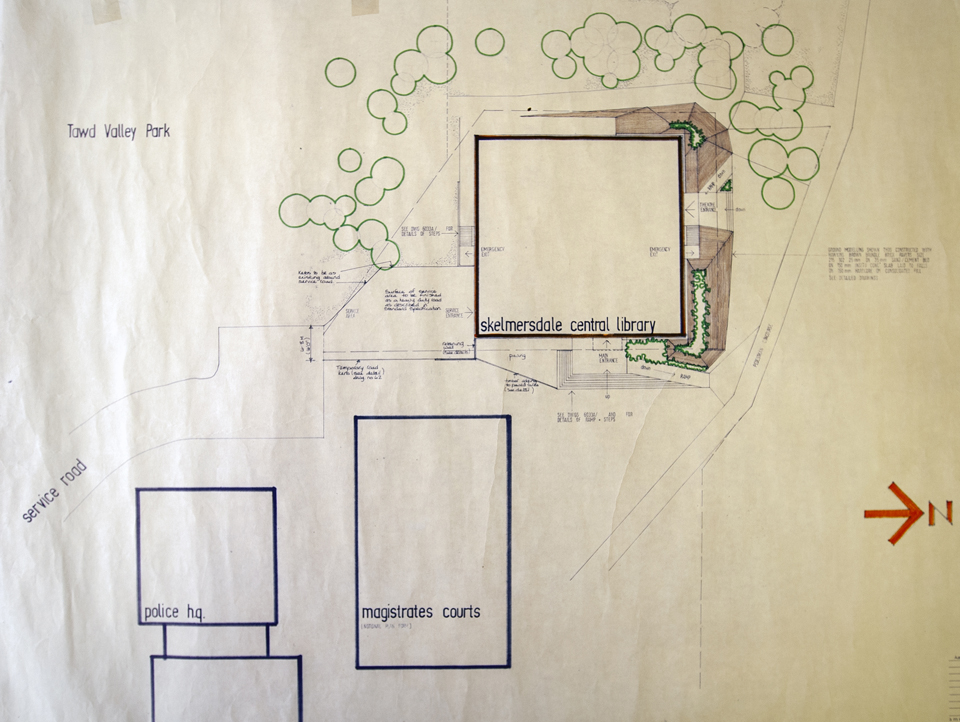

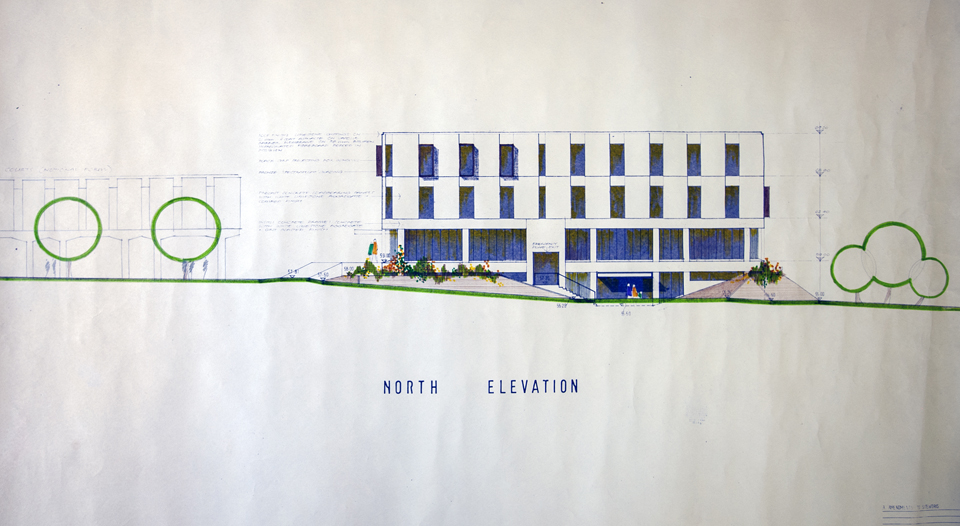

In Skelmersdale, the design for certain civic buildings fell to Lancashire County Council, rather than the New Town Development Corporation. Amongst these were the police station, fire station, schools and the library, designed by Roger Booth, Lancashire County Architect and County Librarian Alan Longworth. The decision to build a Central Library was made after consideration of a ‘decentralised system of small branch libraries’. Much spatial thinking was characterised by system thinking that had permeated through UK planning and architectural cultures since the 1950s. It was something of a shorthand for mass production, efficiency and novel technologies that were expected to make things cheaper, faster and better respectively. After rejecting a system of libraries though, the architects turned to a system building, namely Lancashire’s concrete construction system (GRID), which was developed by the R&D group of the County Architect’s Department in collaboration with a private architectural practice, Morrison & Partners of Derby, and the manufacturer [1]. This system was most extensively deployed in the construction of the county’s police stations but was primarily tested in the realm of school design. Four of the textured concrete panels that would eventually form the county’s most fortified monoliths were first assembled in the playing fields of a school in Accrington, which was under construction as the R&D group were at work. This prototype remains in place to this day and had a roof and door applied to act as a shed, referred to in the 1971-3 review of the department’s work as ‘surely the most expensive groundsman’s store ever constructed!’[2] The intent was to design and develop a load-bearing concrete panel that would transfer its own dead load externally through the façade and reduce the need for internal columns, adding to the established advantages inherent in system building with an attempt to minimise extraneous structure and to free internal planning – this suited both contemporary pedagogic approaches in schools and office layouts informed by bürolandschaft planning. The advantages were discussed in terms of flexibility, the ability to achieve consistent environmental conditions, reduced maintenance, and the exclusion of noise and dust. The windows were conceived as either punched apertures or as slots between panels. Reports of the county architect indicated that the lack of natural daylight was a secondary concern to the architects at the time – glazing, in this context, was considered in terms of its poor thermal performance. The system was variously labelled the ‘Heavy Concrete Method’, ‘Lancashire Concrete Method’ as well as its earlier name, ‘GRID’, and was proposed as suitable for buildings of three to seven storeys. Gladly, the library used more glazed panels than the police stations and its outward appearance is not quite as brutal as its concrete cousins. The building was designed to account for a future population projection of 80,000, but Skelmersdale only had half that number of residents as it was completed. As a result, the additional space in the library was used to provide a small library facility for the nearby college. The ground and lower ground floors were cast in-situ concrete structures to account for a shift in levels across the site, above this, the concrete panel system acted structurally. Heavier, noisier and short-stay activities and functions were kept to the lower levels, whilst the upper floors held quiet study, reference and long-stay areas. The solid, near cuboid building contrasts starkly with those designed by Ronald Bradbury for nearby Liverpool suburbs.

[1] Industrialised Building Systems & Components, February 1966, pp.73-80; System Building and Design, November 1967, pp.13-22, 19. Morrison had also developed an earlier aluminium system for school buildings known as ‘Derwent’. See Saint A, (1987) p.129.

[2] County Architect’s Report, April 1971 to March 1973, Lancashire County Council, p.117. CC/GR/22, Lancashire County Record Office.