Paddington Maintenance Depot

1968

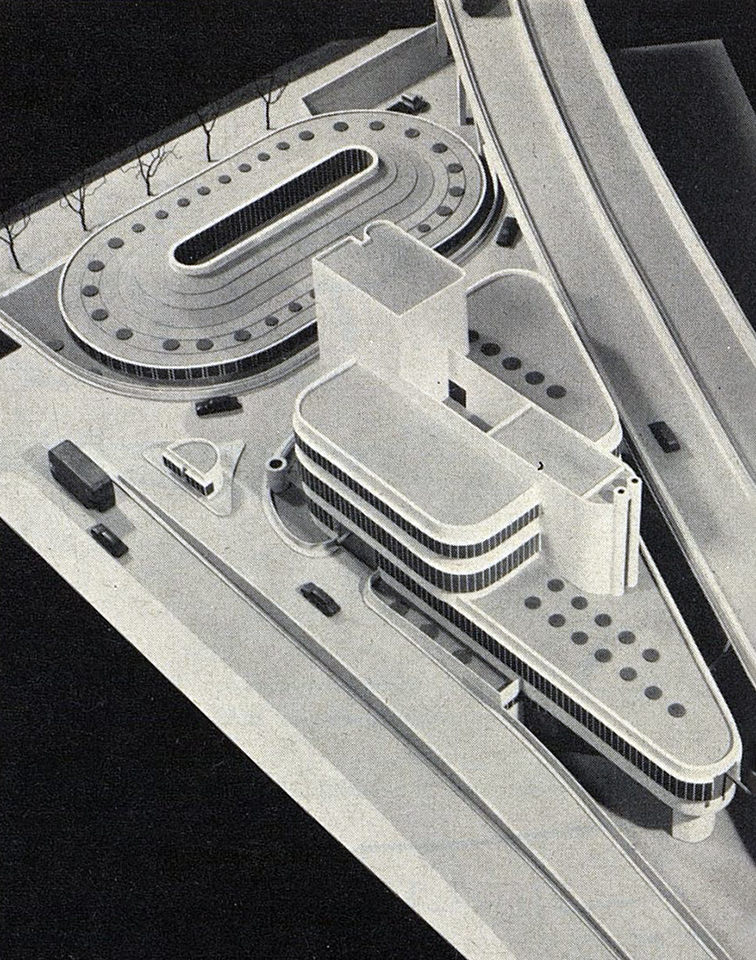

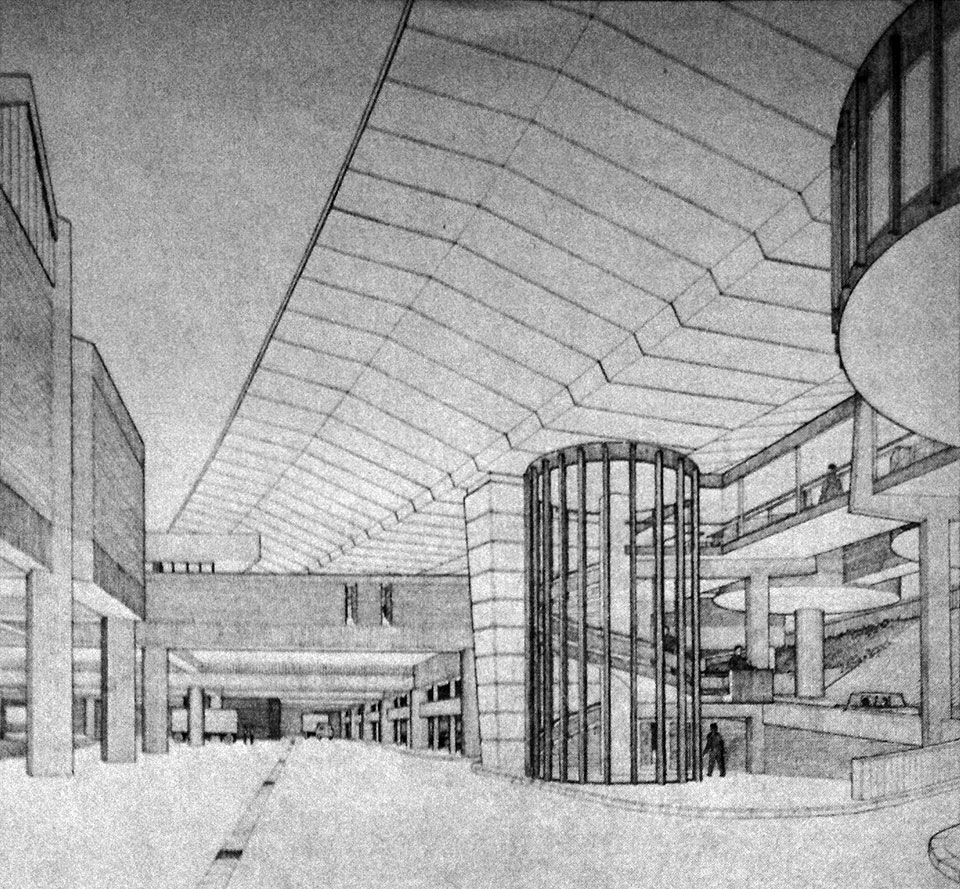

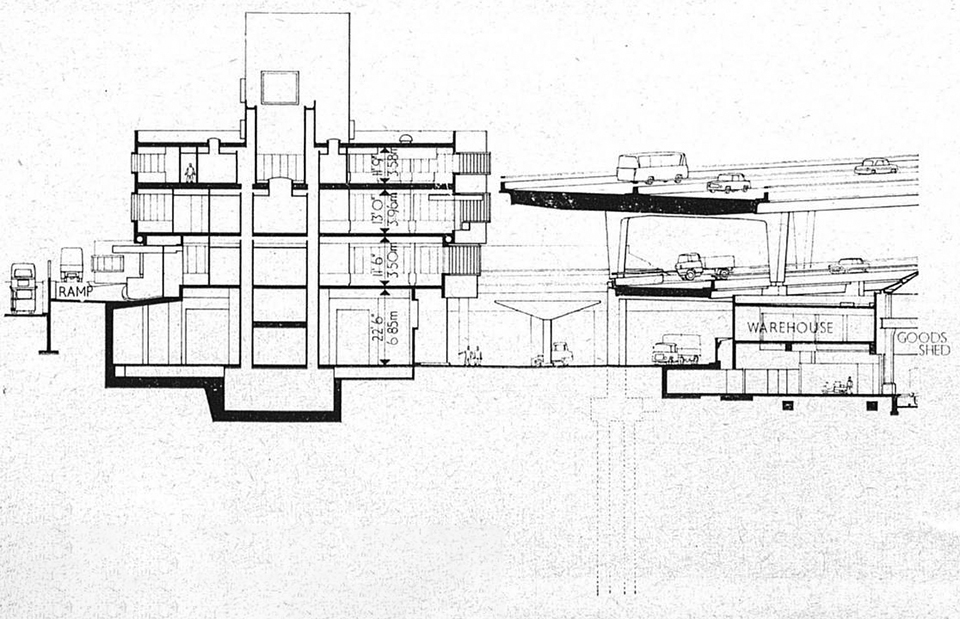

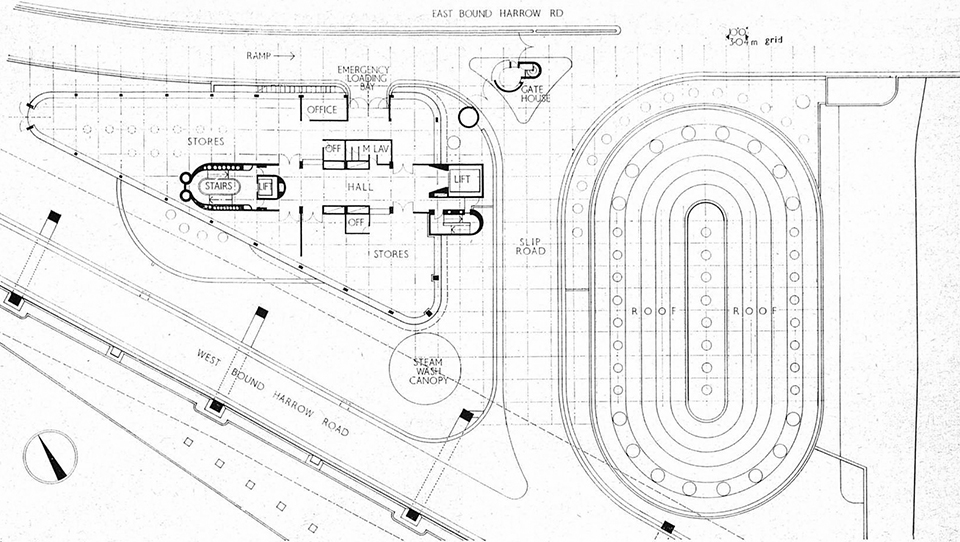

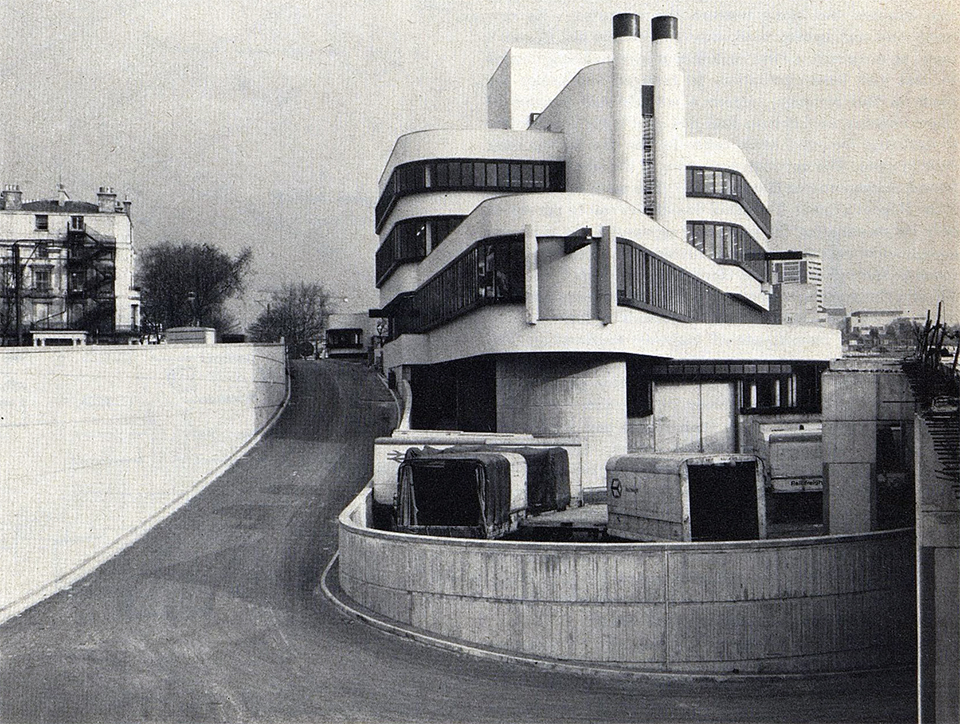

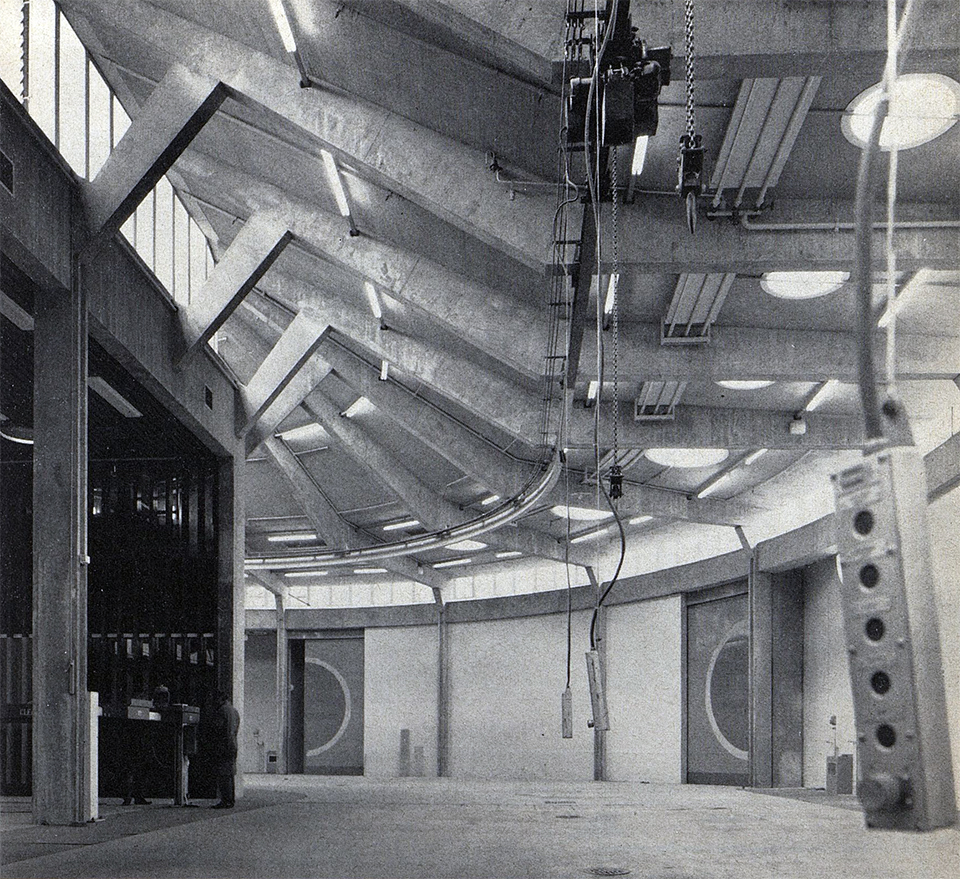

Paul Hamilton, for Bicknell and Hamilton in collaboration with Hubert Bennett. Born in 1924 in Vienna, Austria, Paul Albert Herschan arrived in the U.K. in 1939 as part of the Kindertransport scheme and remained after his parents were killed in the Holocaust. He joined the Alien Pioneer Corps of the British Army in 1942, replacing his original surname with the non-Germanic ‘Hamilton’. After studying at the Architectural Association from 1947-53, he worked for the London County Council before beginning work at British Rail’s Eastern division often alongside his fellow former AA student John Bicknell – with whom, in 1963, he would form a partnership. Through working closely with British Rail, Bicknell and Hamilton produced several notable buildings, heavily influenced by the nationalised railway policies and governmental legislation regarding infrastructure and urban growth of the time. One of their best-known is the Paddington Maintenance Depot. A rare example of modern and innovative infrastructural railway architecture, it was built after the 1968 Transport Act, a piece of legislation put forward by Harold Wilson’s Labour government granting the railways financial assistance. This underlined the period of closures brought about by Beeching and initiated a period of stability, improving the railway’s funding streams and allowing the system to function more as a national service rather than a business. The scheme lies between several different parts of the transport landscape, weaving underneath motorway slip roads and over railway tracks in a design said to resemble a ‘landlocked ship’ [1] - this nautical form possibly a nod to the Paddington Basin canal adjacent. The design is composed of two joined blocks, the west block housing administrative offices and the east block, a single-storey oval-shaped garaging area for the maintenance of British Rail’s road support vehicles. The garage is a reinforced concrete structure with a coved shell concrete roof on dramatically arched cantilevered beams springing from the side walls. The space is lit by clerestory glazing and pierced portholes in the roof. The west block is sandwiched between an access slip road and the main carriageway of the elevated A40 Westway, while the eastern block is bordered by motorway, street and canal - the two blocks meet at ground level. The triangular plan of the west block rises from its tarmac shackles and a full band of ribbon windows provide a stark eye level encounter between office workers and drivers from the second floor. The tallest part of the building is the twinned towers of the stair tower and boiler flues. This steadfast monolith amongst an entanglement of roadways, sits as a node of interchange amidst the infrastructural landscape of inner London, turning ‘potential waste’ to ‘valuable purpose’ and achieving ‘architecture of impressive value’ [2]. Alongside Paul Hamilton were B.H. Crockford, D.L. Bates, D.P. Quinn and Walter Stahel. Structural engineers were G. Maunsell and Partners. It was Grade II* listed in 1994.

[1] Architectural Forum, May 1969, pp.64-67

[2] Architects’ Journal, 18 December 1968, p.1466