Underley Hall Chapel

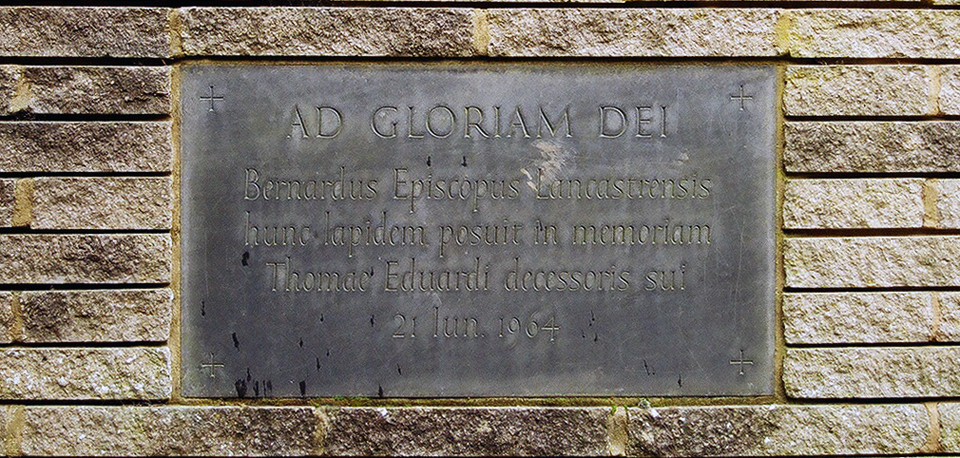

1966

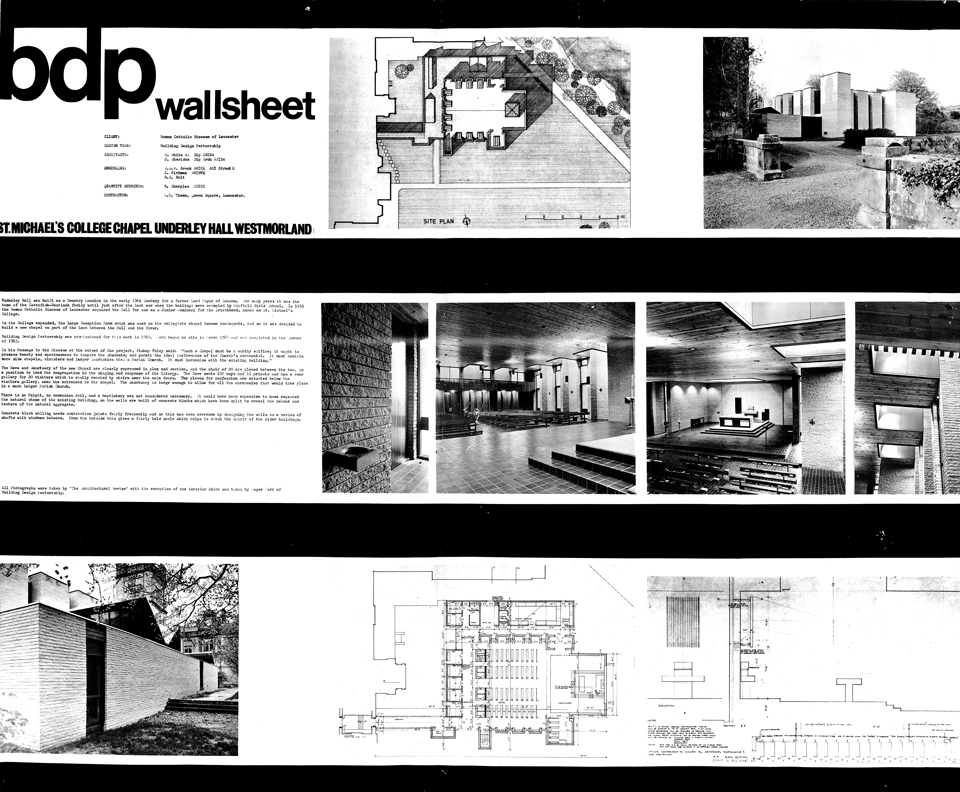

Tucked away in northern Lancashire is a little known chapel by BDP, built between 1964 and 1966 and annexed to a country mansion. The chapel was commissioned by the Lancaster Diocese shortly after they purchased the estate in 1959, to run a junior seminary for Catholic priests; St. Michael’s. Nikolas Pevsner, in 1968, described the chapel as “easily the best recent ecclesiastical building in the country”. The site was, until recently, a residential school for young people with behavioural problems and as such may only be accessed by prior arrangement.

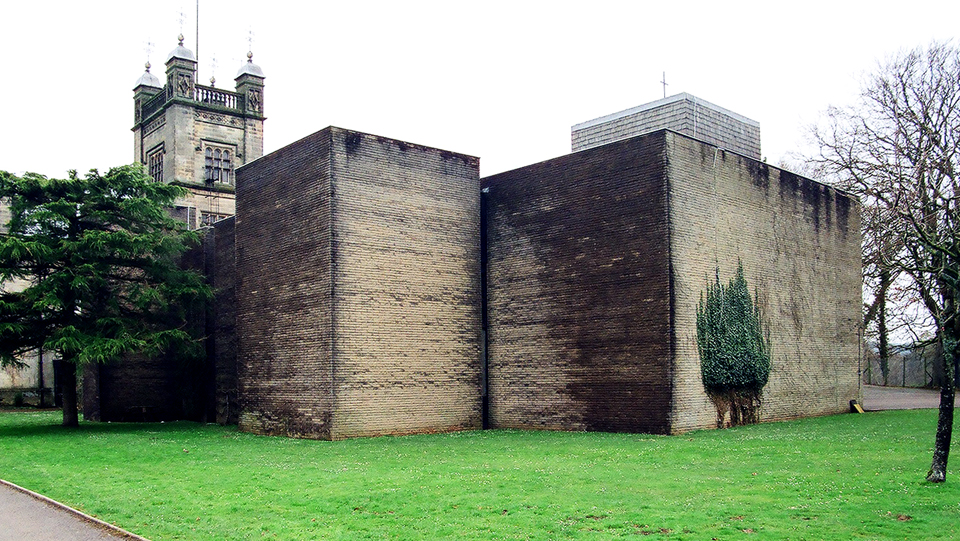

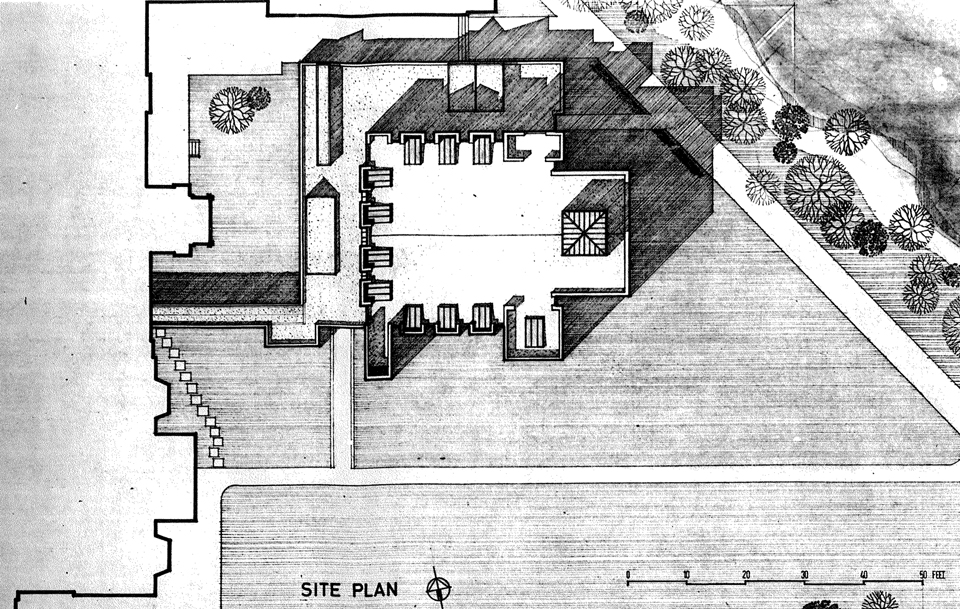

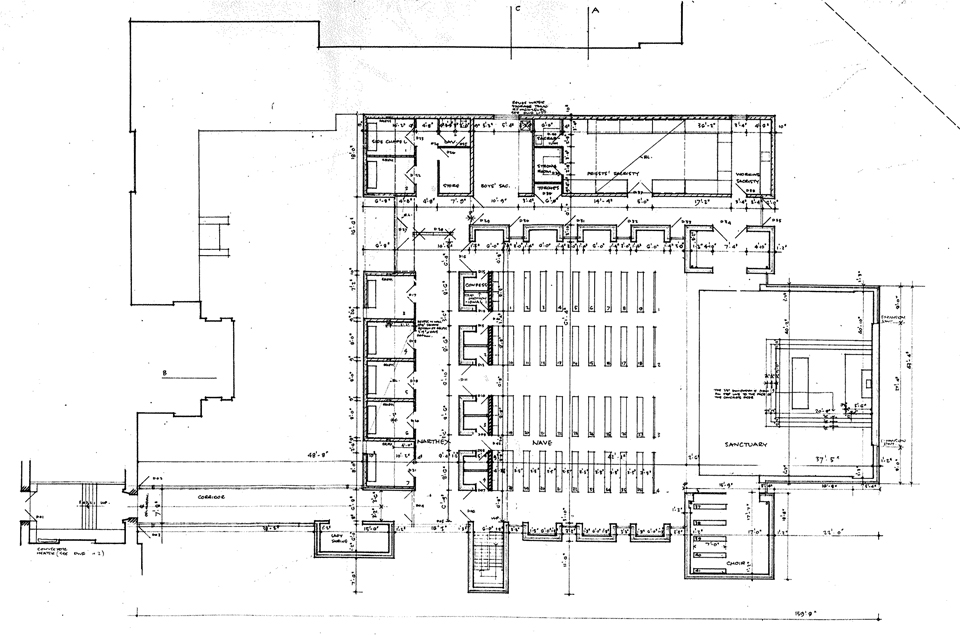

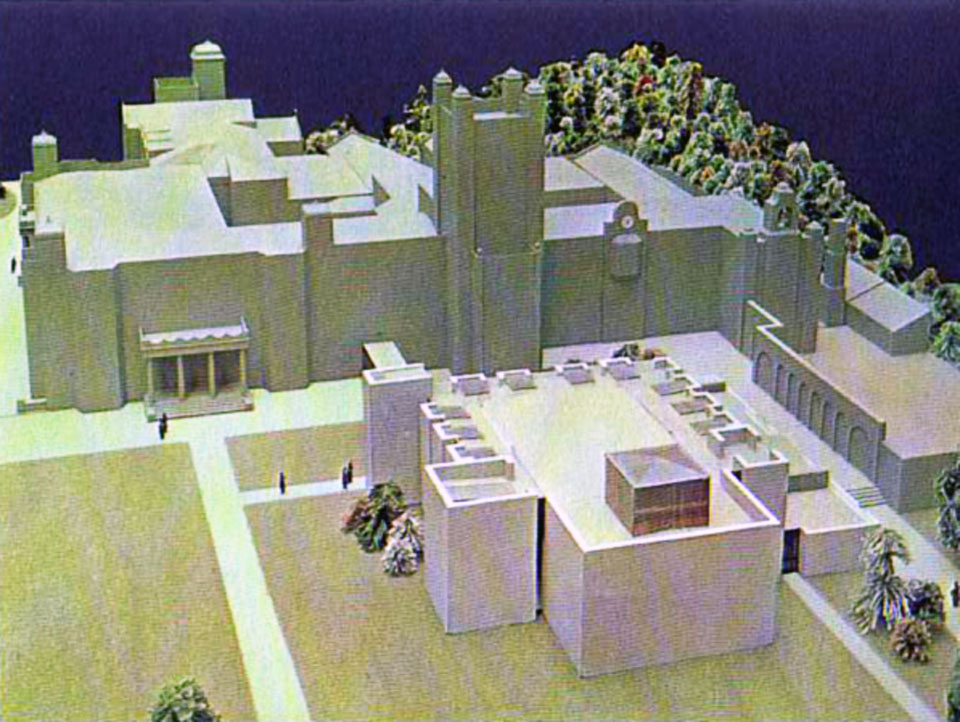

The principal building on the estate is the rather imposing Underley Hall, built over the footprint of a former house within an estate established since the Sixteenth Century. It was constructed after 1825 in a Jacobean Revival style for Alexander Nowell and designed by George Webster. The 1960’s chapel sits to the east of the main hall, between it and the River Lune and was designed by William (Bill) White and John Sheridan, assisted by a full compliment of consultants from the progressive, multi-disciplinary offices of Building Design Partnership in Preston.

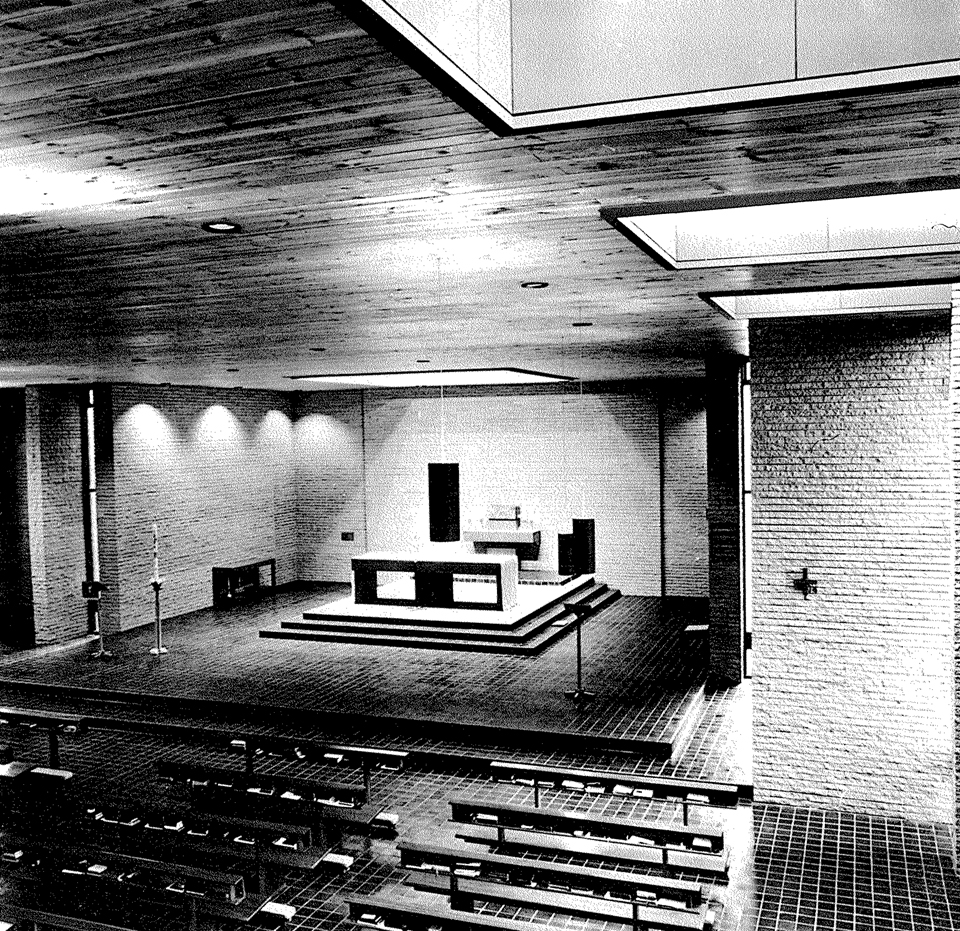

The planning of the scheme and the distinctive cellular nature of its elements were informed by both designated programme and material selection. The demand for more side chapels than would be requisite in a parish church, delivered a strip of seven cells for private contemplative prayer to the rear of the main ecumenical space. These can be accessed with no interruption to services and are subtly composed to reinforce solitude and calm. A mixture of long windows or roof lanterns either facilitate connection or separation from external stimuli, and a single step up within each chapel further promotes the isolative qualities of these spaces. They are sparsely decorated, in keeping with the sobriety of contemplative prayer.

Budgetary restrictions meant that the material palette, whilst restrained does not bear the quality hallmarks of the building’s composition. Both the internal and external walls are constructed of concrete paving “split to reveal the colour and texture of the natural aggregate”. It was intended that this was complimentary to the stone of the existing hall. The settling and movement properties of the concrete were effectively unknown and lead to the ‘C’ shaped bays separated by full height windows. The floor is finished throughout in quarry tiles and fittings and linings are almost exclusively in stained softwood.

Most of the original fabric remains intact, though the altar and congregational spaces have been subdivided with temporary partitions, into a store and gymnasium respectively. The simple confessionals, which sat beneath the visitor’s gallery, have also been dismantled. The roof construction is cleverly afforded an airy presence by the use of lanterns that occupy the spaces between the deep trusses and cast a soft light to the side and rear walls. Above the Sanctuary is another huge roof lantern that would have undoubtedly drawn focus to the altar. Externally this is expressed as a rather squat tower, clad in hung slates.

The connection to the existing hall is by a glazed corridor, described as a cloister, but not perhaps evoking the monastic spirit that one would traditionally associate with the term. Where the new and old meet a neat junction composed of cleanly engineered timber components visually frames and stretches the event of threshold transition. The necessity for this route to perform as a connective element is revealed, as embedded within the historic fabric is a further component of the scheme; a small dining room, created from the infill of an internal courtyard to the main hall. The space has recently been stripped back to reveal the original finishes as intact; wall and floor linings and a beautifully engineered truss system. The trusses are formed from slender timber sections and tension rods to facilitate a continuous band of clerestory glazing. The quality of the diffused light even on a grey day is soft and calming and the muted palette of the rest of the fittings gives the space an appropriately ethereal, time capsule quality.

At the outset, Bishop Foley, in his commissioning address said, ‘Such a Chapel must be a worthy edifice; it ought to possess the beauty and spaciousness to inspire the students…it must harmonise with the existing building’. The beauty and spaciousness remain clear to read, despite the modifications; the simple material palette and the crisp detailing of the rigourously orthogonal geometries is beautiful and the proportions throughout present spatial qualities that feel appropriately considered. The question of harmony is perhaps one that would yield an alternative proposition; the current edict concerning the contrast of new additions or interventions against historic fabric may not have resulted in the material choices presented here. The mass of the building, however, is a different consideration and the relationship between the head of the structural piers and the datum of the stone cornice to the existing building is one that would likely be repeated. The future of this building is entirely dependent on the tenure of the Headmaster. Currently a sensitive attitude to the retention of the former chapel prevails.